Neck Radiotherapy Increases the Risk of Syncope During Awake Airway Management: A Report of Two Cases-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF HEAD NECK & SPINE SURGERY

Abstract

Radiotherapy for head and neck cancer may causes

baroreflex dysfunction and can lead to syncope. Syncope is usually a

benign clinical condition and self-limit. However, in patients with

difficult airway their spontaneous recovery can be interrupted by the

significant hypoxia caused by airway obstruction. This might lead to

situation of cannot intubate and cannot oxygenate requiring emergency

surgical airway. Here we report two cases in which previous radiotherapy

treated patients developed syncope during preparation for awake

intubation resulting in emergency surgical access.

Keywords: Airway Syncope Neck radiotherapy Awake airway management

Abbrevations:

TLOC: Transient Loss of Consciousness; NRT: Radiotherapy to The Neck;

BP: Blood Pressure; HR: Heart Rate; CICO: Cannot Intubate, Cannot

Oxygenate; OR: Operating Room; BPM: Beats Per Minute; ETT: Endotracheal

Tube; SCC: Squamous Cell Carcinoma; IV: Intravenous; LMA: Laryngeal Mask

Airway

Introduction

Syncope is defined as Transient Loss of Consciousness

(TLOC) owning to brain hypoperfusion. It is characterized by quick

onset, short duration and is self-limited. It is generally a benign

clinical condition and has a reported overall mortality rate of 0.28%

from all causes [1]. Clinical reports have shown that Radiotherapy to

The Neck (NRT) for cancer treatment causes impairment of the baroreflex

response and results in baroreflex dysfunction. Studies have also

demonstrated a positive correlation between NRT and syncope [2,3].

Although full compensation for baroreflex dysfunction may be achieved in

daily life, these individuals may have a decreased tolerance to

emotional or physical distress resulting in exacerbated Blood Pressure

(BP) and Heart Rate (HR) changes with stimulation. We report two cases

in which patients developed TLOC during airway preparation for awake

intubation, resulting in the situation of “Cannot Intubate, Cannot

Oxygenate (CICO)”, and their airways were managed by emergency surgical

access.

Case 1

62-year-old, 78kg female with a past medical history

of controlled chronic hypertension and recurrent tongue cancer presented

for direct laryngoscopy, tongue biopsy and possible tracheostomy. The

patient underwent a partial glossectomy 13months previously due to

primary oral tongue cancer followed by bilateral neck radiotherapy.

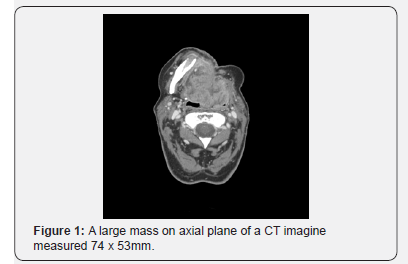

Tumor assessment revealed a large mass extending from the right base of

the tongue to the ipsilateral vallecular region, (Figure 1) but no

hypopharyngeal or laryngeal airway obstruction. Awake flexible scope

intubation via nasal approach was planned. Upon arrival Operating Room

(OR), the patient was placed on the OR table with the head elevated 30

degrees. Her first BP, HR and room air O2 saturation readings in the OR

were 165/82mmHg, 71 beats per minute (bpm) and 100%, respectively. She

received 2mg midazolam and 50mcg fentanyl intravenously upon arrival to

the OR. Attempted placement of a # 28 nasal trumpet into the nares for

dilation purposes caused significant discomfort as the result

Case 2

58-year-old female with a medical history of well-controlled

chronic hypertension and right vocal fold recurrent Squamous

Cell Carcinoma (SCC) presented for a total laryngectomy. Her

primary laryngeal cancer was treated with bilateral neck

radiotherapy two years prior to the surgery. Patient denied any

history of cardiovascular disease. She presented with a weak

and hoarse voice, but no difficulty breathing. She had a BMI of

38kg/m2 and neck circumference of 39cm. Airway assessment

revealed a Mallampati 3 airway without significant abnormality

in any other routine airway assessments. Video laryngoscopy

performed one week prior to surgery revealed an exophytic

tumor growing on her right vocal cord with immobilization

of the ipsilateral true vocal folder. However, the airway was

unobstructed. Based on the above findings, an awake flexible

scope intubation was planned. The patient had a baseline BP,

HR, and oxygen saturation of 148/72mmHg, 82 bpm and 98%

on room air, respectively. In the OR, the patient was placed in

the siting position with 2 L/min of O2 through a nasal cannula.

While placing monitors, the patient became pale and then

became unresponsive. The pulse oxygen waveform showed pulserate of 30s bpm with weak pulse by palpation, but her BP could

not be obtained by sphygmomanometer. Ephedrine (15mg)

was immediately administered Intravenously (IV) followed by

200mcg of phenylephrine. Despite the efforts of mask ventilation

with 100% oxygen, her O2 saturation continued falling. Trismus

was also evident when attempting insertion of an oral airway.

Subsequently, a Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA) was placed

after intravenous administration of 120mg succinylcholine, but

no improvement of oxygenation was achieved. An emergent

tracheostomy was performed at O2 saturation in the low 80s%

by the surgeon. Thereafter, the patient was allowed to regain

consciousness and exhibited a normal neurologic assessment.

Surgery was then continued and completed in three hours.

Postop 12 leads EKG showed a normal sinus rhythm with HR of

68 bpm. The cardiology consult suspected a vasovagal syncope

as the cause of TOLC. No further evaluation was performed. In

PACU visit, patient had no recollection of the intraoperative

events. She underwent an uneventful hospitalization and was

discharged from the hospital on post-operative day #5.

Discussion

The sequential events developed in the two cases resembled

a cycle of reflex syncope. In these two cases, previous NRT

predisposed patients to potential baroreflex dysfunction.

Emotional distress and/or additional painful stimulation played

an important role in triggering the hemodynamic instability by

exacerbated BP and HR changes resulting in TLOC. However, the

self-recovery was interrupted by significant hypoxia caused by

airway obstruction. Without quickly establishing invasive airway

access, both cases may have resulted in significant patient

morbidity.

In patients with reflex syncope, stimulation from the

circulatory and visceral receptors to the brain via the

corresponding somatic sensory pathway, glossopharyngeal or

valgus nerves, strong emotional distress may directly activate or

facilitate activation of this reflex. The efferent paths consist of

the valgus nerve to heart and sympathetic fibers to the heart and

vessels. The degrees of vasodepressor and bradycardia, or both,

result in varying levels of manifestations. Most syncope attacks

occur in the upright posture reflecting the mechanism of central

hypovolemia in loss of consciousness and memory dysfunction

during an attack [4]. In a healthy individual, the functional

integrity of baroreflex plays a protective role in preventing

syncope. Impaired baroreflex is a mechanism resulting in

inability of sympathetic response to systemic hypotension [5,6].

A previous study demonstrated that impaired baroreflex predicts

the development of syncope during tilted test [7].

Baroreflex failure resulting from NRT is a rare clinical

entity. However, radiotherapy-induced baroreflex dysfunction

is common. Lack of heart rate and blood pressure response to

valsalva maneuverer and vasoactive challenging tests in patients

undergone NRT were found in all the patients in the study [8,9];and decreasing hemodynamic responses to surgical stimulations

in patients with NRT undergoing general anesthesia was also

reported [10]. Therefore, the patients with full compensation

of dysfunctional baroreflex in their daily life may develop

baroreflex decompensation under certain circumstances (the

triggers) resulting in loss of hemodynamic autoregulation and

episode of syncope.

Despite detrimental effects of TLOC developing at critical

moments, a routine test of baroreflex function in asymptomatic

patients is not practical. Therefore, carefully inquiry into

the history of fainting or near fainting in patients who have

undergone NRT is important to recognize the patients with

increased risk of syncope. During airway management,

emotional distress and anxiety should be controlled before the

onset of an awake intubation procedure. Every effort should be

made to prevent central hypoperfusion resulting in TLOC and

collapse of airway by avoiding prolonged erect position and

promptly treating hypotension and bradycardia. To manage a

difficult airway, one must be aware that repeated stimulation

of the glossopharyngeal nerve distribution (posterior 1/3 of

tongue) by airway instrumentation may worsen the symptoms

and prolong the recovery period; therefore, the benefits versus

the risk ratio of technique chosen to manage the airway must be

carefully considered. Nevertheless, managing a difficult airway

with a concurrent sudden onset event is challenging. Prevention

and early treatment are key to success and the avoidance of

catastrophic results.

To know more about Open Access Journal of

Head Neck & Spine Surgery please click on:

To know more about Open access Journals

Publishers please click on : Juniper Publishers

Comments

Post a Comment