Biopsy-Proven Brain Metastases from Prostate Adenocarcinoma on 68Ga PSMA PET/CT: Case Series and Review of the Literature-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF HEAD NECK & SPINE SURGERY

Abstract

Prostate cancer brain metastases are extremely rare

and typically occur at a late stage in the course of the disease with

poor prognosis. However, the incidence is rising as novel antiandrogens

and radionuclide therapy prolong survival and change the natural course

of the disease. Surveillance imaging of the brain is not the current

standard of care. We present two cases of patients who had brain

metastases from prostate adenocarcinoma initially detected on prostate

specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positron emission tomography/computed

tomography (PET/CT) and also provide a review of the epidemiology,

pathogenesis, imaging features, pathogenesis and current treatment

modalities of prostate cancer brain metastases. Our patient with

multiple brain metastases is still alive three and a half years post

initial diagnosis after being successfully treated with surgery,

androgen deprivation therapy and radiosurgery. This is the longest

survival time of any patient with multiple brain metastases and systemic

disease. We postulate that overall survival will increase with earlier

detection and treatment of brain metastases from a prostate cancer

primary and that scanning vertex to mid-thigh should be standard

practice with PSMA PET imaging.

Keywords: Brain metastasis; Prostate cancer; Neuroradiology; Ga68PSMA PET/CT

Abbrevations:

PCa: Prostate Cancer; Ga: Gallium; PSMA: Prostate Specific Membrane

Antigen; PET/CT: Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography; MRI:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SRS: Stereotactic Radiosurgery; Gy: Gray;

PSA: Prostate Specific Antigen; PAP: Prostatic Acid Phosphatase; ADT:

Androgen Deprivation Therapy

Case 1

A neurologically intact 66-year-old man presented for

a Ga68 prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positron emission

tomography (PET) scan due to a rising prostate specific antigen (PSA)

level of 7.4ng/ml thirteen years after a successful radical

prostatectomy for a Gleason 7 prostate cancer (PCa).

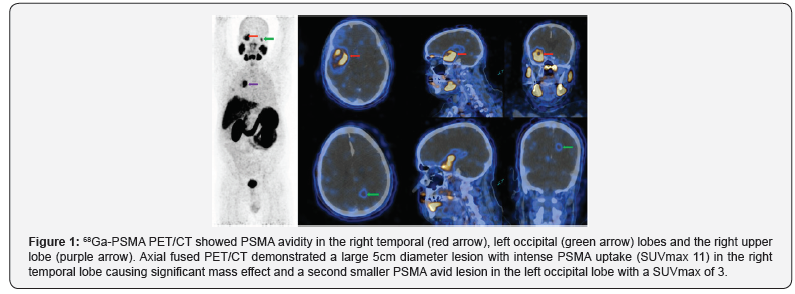

PSMA demonstrated an unusual distribution of disease with

intensely PSMA avid foci in an enlarged mediastinal lymph node,

within small lung nodules and in two PSMA avid brain foci within

the right temporal and left occipital lobes. Brain MRI revealed a

large 6.5cm complex enhancing lesion in the right temporal lobe

compressing the temporal horn and the body of the right lateral

ventricle. The cystic component of the mass showed no restricted

diffusion. A second 1.1cm lesion was noted in the left occipital

lobe superior to the ventricular trigone with peripherally

restricted diffusion and increased diffusibility centrally (Figure

1).

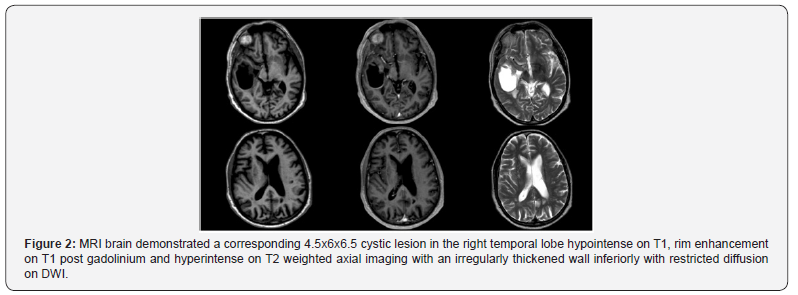

The patient underwent a right temporal craniotomy and

excision with gross total resection achieved (Figure 2). Histology

confirmed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma with positive

immunohistochemistry for PAP and PSA. The patient received

adjuvant stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to the right temporal

lobe cavity, left parietal lobe mass and hormonal manipulation

with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Nine months postoperatively, the patient remained clinically

well with no neurological symptomology and undetectable PSA

with ongoing ADT. MRI brain confirmed no recurrence in the

right temporal lobe cavity but an increase in the size of the left

occipital lobe lesion. PSMA PET/CT demonstrated mild persistent

increased PSMA avidity in a solitary focus in the left occipital

lobe. Complete metabolic response at all other metastatic sites

with no new disease found. The patient was treated with further

SRS (14Gy in a single fraction) to the region of PSMA avidity in

the left occipital lobe. Three and a half years post operatively, he

remains well with good disease control.

Case 2

A 71-year-old man with metastatic castration resistant

prostate cancer previously treated with external beam

radiotherapy, ADT, radium 223 therapy and docetaxel presented

with a three-week history of increasing confusion and ataxia.

MRI brain revealed a well circumscribed 2.4 x 2.0cm

cystic, enhancing mass in the left para-median thalamus and

midbrain compressing the cerebral aqueduct and five other

lesions throughout the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres. The

thalamic cyst was biopsied and aspirated, but his symptoms

persisted. Histologic examination confirmed metastatic prostatic

adenocarcinoma. He was treated with whole-brain radiotherapy

but passed away two months following radiation treatment.

Intraparenchymal metastases from a prostate

adenocarcinoma primary is rare and only occur in an estimated

0.6-1.9% of patients [1-3]. However, the incidence is increasing

as novel antiandrogens and radionuclide therapy prolong

survival and change the natural course of the disease.

On the 1st of May 2018, a comprehensive literature search

examining peer-reviewed, English language articles from 1982

to 2018 was performed on multiple databases, yielding 1286

articles. These articles were reviewed and selected for studies

that met the following inclusion criteria;

a) Patients with intraparenchymal metastases from

prostate adenocarcinoma proven either on antemortem

resection or stereotactic biopsy and

b) Metastases confirmed on CT or MR brain imaging.

Additional relevant studies were also searched manually in

the reference lists of identified studies and by using the “related

articles” tool in PubMed. Patients with dural or skull-based

tumours extending into the brain were excluded from the review.

We found 1286 articles and considered 29 articles eligible. A total

of 47 men with brain metastases from prostate adenocarcinoma

origin confirmed on radiological imaging and antemortem

biopsy was thus identified in the literature (including our 2 cases

reported here).

Discussion

Epidemiology

For patients with brain parenchymal metastases from

prostate adenocarcinoma of any subtype, the mean at diagnosis

of brain metastasis was 66.3 years (range, 48-88 years) and the

median age was 66 years.

35 of the 47 men had known prostate adenocarcinoma at

the time of their cerebral metastasis diagnosis whilst for 12

men this was the initial presentation of their primary prostate

tumour. The mean age at diagnosis of brain metastasis for men

with known prostate cancer (PCa) was 65.5 years (range, 48-

88 years). In patients with cerebral metastases as the initial

presentation of their primary tumour, the mean age of brain

metastasis diagnosis was 66.4 years (range, 56-75 years).

Hatzoglou et al. [4] study of 7 patients with biopsy proven

brain metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma was not

included as we were unable to differentiate the patients’ mean

age at diagnosis of brain metastasis from other patients in

their cohort who had biopsy from other sites of distant disease

confirming metastatic PCa.

Timing and symptoms

Patients with metastatic disease to the brain developed

disease an average of 4.4 years (range, 3 days to 13 years) after

the initial diagnosis of their PCa. New therapies increasing

overall survival time gives the tumour enough time to develop

brain metastases, that is usually a late event of the disease [5,6].

Neurological manifestations on presentation varied

according to the anatomical site with most metastases situated

in arterial border zones and the junction between the cortex

and subcortical white matter. The majority of patients (95.7%)

presented with overlapping neurological signs and symptoms.

22 patients presented with headache, the most common

presenting complaint at diagnosis followed by motor weakness

(n=16), ataxia (n=13), confusion (n=10), seizures (n=8), speech

impairment (n=7) and visual field disturbances(n=4). In the

two neurologically asymptomatic patients, the brain metastases

were diagnosed on surveillance imaging after a rise in PSA.

In 11 patients, the brain was the sole site of distant metastasis

[7-16]. In patients with metastatic disease, the most common

extra prostatic sites were bone (61.7%), lungs (26.4%), liver

(16.1%) and lymph nodes (13%).

Lesion characteristics

A total of 73 metastases was seen in the 47 patients. 39

patients (83%) had a solitary brain metastasis whereas the other

8 patients (17%) had multiple metastases. Four patients (8.5%)

had two metastases and 4 patients (8.5%) had 6 or more brain

metastases.

The frontal lobe (n=15) and the cerebellum (n=15) were

the most prevalent sites of metastases followed by the parietal

(n=14), temporal (n=12) and occipital (n=6) lobes. One patient

had a solitary metastasis in the temporo-parietal lobe and one

case involved the parieto-occipital lobe. Five patients had 6

metastases in the brainstem. Two cases involved the cavernous

sinus and one patient (our case) had a metastasis in the thalamus.

49 patients (67.1%) had parenchymal metastases located in

the cerebral hemispheres which corresponds to what is known

about the distribution of parenchymal metastases from other

primary cancers.

15 patients (20.5%) with brain metastases from PCa origin

were found in the cerebellum and only 8.2% of metastases

were found in the brainstem. This distribution of intracranial

metastases is similar to metastases from breast, lung and

melanoma where approximately 15% of metastases are found

in the cerebellum. Brainstem are uncommon sites especially

for solitary lesions and account for <1% of all brain metastases.

Interestingly 3 patients (4.1%) in our review of all the literature

to date had solitary metastases in the brainstem [8-9,17].

31 patients (68.9%) had one or more metastatic brain

lesions in the supratentorial compartment [7,9-13,16,18-25],

11 patients (24.4%) in the infratentorial compartment [8-

10,13-14,17,23,26] and 3 patients (6.7%) in both compartments

[27-29]. Two patients with lesions in the cavernous sinus were

excluded.

Intraparenchymal cerebral metastases from prostate

adenocarcinoma are rare and multiple metastases without

systemic disease is exceedingly uncommon. In the largest case

series to date of 16280 patients with brain metastases from

prostate cancer by Tremont-Lukats et al. [1] only 103 patients

(0.6%) had parenchymal brain metastases. In most cases the

metastases were singular (86%) and supratentorial (76%).

Only 3 patients (2.9%) of the cohort had both infratentorial and

supratentorial metastases.

A more recent case series by Hatzoglou et al. [4] found 10

patients (47.6%) of their cohort had both supratentorial and

infratentorial metastases. This is significantly higher than

other case series to date and is likely due to MRI images from

Hatzoglou’s case series being reviewed by a neuroradiologist

versus some cases in our review being limited to only single

slice images of patients’ CT or MRI which limits our ability to

ascertain the distribution of lesions outside of our two cases.

Gross pathology

Parenchymal metastases are generally round, discrete lesions.

The metastases in our review had variable peritumoural oedema,

necrosis and mass. Non-uniformity in the spatial distribution

of the parenchymal metastases suggests that vulnerability to

metastases differ according to its anatomical location. Our review

found parenchymal metastases from PCa had a predilection

for the frontal lobe and cerebellum (n=15, 20.5%) which is

consistent with other large case series which found 17-25% of

metastases from PCa were found in the cerebellum [1,4]. Unlike

melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and choriocarcinoma which are

particularly prone to developing intratumoural haemorrhages,

brain metastases from PCa was not found to have intratumoural

haemorrhage on imaging or histopathology. All of the patients

included in our review had biopsy confirmed adenocarcinoma

with positive immunohistochemical staining for PSA and PAP.

Imaging features

The cerebral metastases had highly variable imaging

appearance and was difficult to differentiate from metastases

originating from other primary tumour sites. Eight patients in our review only had CT imaging of their cerebral metastases

[7,9,18-21,26]. On non-contrast CT imaging, most metastases

were isodense to slightly hypodense relative to grey matter.

The majority of parenchymal metastases enhanced strongly

following contrast administration.

On axial T1-weighted MRI, most of the parenchymal lesions

were mildly hypointense. On post gadolinium imaging, nearly all

of the non-haemorrhagic metastases showed enhancement with

patterns of disease varying from solid uniform enhancement to

nodular or ring like lesions. FLAIR imaging also demonstrated

significant variability in lesion cellularity, presence of

haemorrhage and amount of peritumoural oedema. On diffusion

weighted imaging (DWI), well differentiated adenocarcinoma

metastases generally showed no diffusion restriction compared

to highly cellular metastases which demonstrated diffusion

restriction.

Cystic intraparenchymal metastases from PCa are rare with

only eight cases documented in literature to date, including our

two patients [11,19,22-23,27,30]. Five patients had solitary

cystic lesions and three patients had multiple cystic lesions.

Intralesional restricted diffusion was present in both our

patients.

Unlike true intraparenchymal cerebral metastases of

prostate adenocarcinoma origin, prostate cancer is the second

most common primary after breast cancer to metastasize to the

dura [5] and poses a radiological diagnostic challenge especially

when it presents as a solitary lesion which can be mistaken for a

meningioma as up to 44% of prostate metastases have a dural tail

[6,31,32]. Distinguishing between the two lesions is important

due to the poor prognosis of intracranial metastatic PCa and the

potential for conservative management versus active treatment

if a radiological diagnosis is made. The incidence of brain

metastases in the most recent series of 16,280 prostate cancer

patients is reported to be around 0.63% [1] which is less than the

1-2.4% incidence reported in autoptic series [3,33-34] with the

incidence of brain metastases being detected in the pre-MRI era

the same as in the post MRI era [1]. We postulate that advances

in MR imaging such as triple dose gadolinium and or 3.0Tesla (T)

MRIs have led to earlier detection of metastases in PCa patients

which allow earlier treatment and thus decrease the potential

for further extraprostatic spread.

Ga68 PSMA PET/CT imaging appears to have superseded F18

FDG PET/CT, CT and MR imaging not only in the staging of PCa

but also in the detection of PSMA-avid disease and is increasingly

being used for restaging recurrent PCa. Our case demonstrates

the importance of scanning from vertex to mid-thigh as albeit

rare, PCa can metastasize to the brain and earlier detection and

treatment correlates directly with improved survival time and

quality of life.

Treatment

All of the patients included in our review underwent

either surgical resection (n=37) or stereotactic biopsy (n=9)

of their intracranial lesion which confirmed their diagnosis

on histopathology. 31 patients (66%) underwent whole-brain

irradiation; 22 patients had adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy

post-surgical resection of their lesion and 9 patients had

whole-brain radiotherapy as their primary treatment. Three

patients had stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to their lesion;

1 in conjunction with whole-brain radiotherapy post-surgical

resection and 2 patients had SRS post-surgical resection of the

main symptomatic lesion. 6 patients had trimodality treatment

with surgical resection, whole-brain radiotherapy and ADT

[10,13,18-19,24-26]. One patient had surgical resection of

the dominant metastasis, SRS to another metastasis and also

received concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (our case).

Surgical resection with adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy

has been the Gold standard for treating solitary metastasis in the

brain. This combined strategy has been evaluated in randomised

controlled trials to significantly prolong survival, alleviate

neurological symptoms and reduce the risk of recurrence when

compared with surgical resection or whole-brain radiotherapy

alone [35].

ADT have also been found to bring both symptomatic and

radiological improvement [36-37] leading not only to an increase

in the overall survival time but also an improved quality of life

and is thus used in both the curative and palliative settings in

patients with prostate adenocarcinoma.

Prognosis

For the 41 patients who had documented survival times from

the initial detection of their brain metastases, the mean survival

time was 13.7 months (range, 3 days to 7 years). The patient

who had the longest survival time of 7 years in our series had a

solitary metastasis in the cerebellum that was resected en bloc

and also underwent a bilateral orchiectomy. Previous case series

have reported a median duration from diagnosis to death of

between 3.5 to 31 months [1,38-39]. Patients without systemic

disease were less likely to have brain lesions [4]. Patients with

brain metastasis as the sole site of extra-prostatic disease had

a mean overall survival time of 24.6 months (range, 1month to

7 years) compared to 13.4 months (range, 3 days to 5 years) in

patients with systemic disease.

We postulate that advances in imaging such as Ga68 PSMA

PET/CT, triple dose gadolinium and 3.0 Tesla (T) MRIs have led

to earlier detection of metastases in PCa patients which allow

the patient to be treated earlier thus decreasing the potential

for further extraprostatic spread and the increased incidence

of patients presenting with brain metastases as the sole site of

disease from their primary PCa.

Solitary brain metastasis has better prognosis than

patients

with multiple brain metastases. The overall survival time for

patients with a solitary brain metastasis was 14.3 compared

to 7.2 months (range, 3 days to 29 months) for patients with

multiple metastases. Our patient had the longest survival time

for a patient with multiple brain metastases of three years likely due

to low volume disease in the brain post-surgical resection

and exceptional response to ADT at the extracranial metastatic

sites.

The mean overall survival time for patients who had surgical

resection was 20.3months (range, 3 weeks to 7 years). The mean

overall survival time for patients who had stereotactic biopsies

was considerably shorter at 6.25 months (range, 1month to

2years). This latter cohort of patients either had disease in

the brainstem that was unresectable [8,17,21] or had multiple

cerebral metastases [13,16,28].

Prior to the introduction of docetaxel in 2002, the incidence

of prostatic brain metastasis from 1994 to 2002 was 0.8%. In the

post-docetaxel era (2002-2011), this incidence had increased to

2.8%. This represents a 239% increase in the frequency of brain

metastases from PCa between the two observation periods [40].

As the appearance of parenchymal metastases usually occurs in

the late phase of the disease process it appears that the increase

in frequency may actually reflect a gain in overall survival. In

general patients are living longer with brain metastases in the

context of PCa due to advances in imaging ability, systemic

treatment and increased surveillance.

Pathogenesis

PCa rarely metastasizes to the brain with the incidence in

large case series ranging from 0.63 to 1.1% [2,41] which suggests

that the brain parenchyma is resistant to the establishment of

metastatic foci by prostate carcinoma cells.

Currently the pathogenesis of cerebral metastases from

PCa is unknown however in summary there are two main

mechanisms postulated;

a) Single step spread via Batson’s paravertebral venous

plexus draining the prostate. Low pressure in the large

venous plexus allowing Valsalva maneuver to generate

enough pressure to reverse blood flow from the IVC to the

venous plexus, avoiding the lung and reaching the CNS.

This mechanism however does not explain the absence of

vertebral metastases and

b) Multi step haematogenous spread where secondary

seeding of tumour cells to the brain occur from a primary

metastatic focus involving the lungs or bones with brain

metastasis usually a late event in the course of prostate

cancer.

Haematogenous metastases have a special predilection for

arterial border zones and the junction between the cortex and

subcortical white matter. PSA is a sensitive indicator of the

presence of disease however serum levels of PSA did not correlate

to the development of brain metastases in our cases which is

consistent with what is found in other case series [11,22].

Conclusion

Intraparenchymal spread of prostate cancer should be

considered in men over the age of 60 years as a treatable

cause of gradual neurological deterioration especially if a

cranial malignancy or hyperostosis is found. The incidence of

intraparenchymal brain metastasis is only expected to increase

due to the longer life expectancy of patients with prostate

adenocarcinoma with novel therapies. Patients undergoing

Ga68-PSMA PET/CT for staging of PCa or when there is a PSA

rise should be scanned from vertex to mid-thigh as albeit rare,

prostate cancer brain metastases is a not to be missed differential

in this particular group of patients.

Consent

The patients provided informed consent to the publication of

their data, de-identified PET and MRI scans. No ethics approval

through an institutional committee on human research was

required.

To know more about Open Access Journal of

Head Neck & Spine Surgery please click on:

To know more about juniper publishers: https://juniperpublishers.business.site/

Comments

Post a Comment