A Rare Case of Traumatic Leptomeningeal Cyst in Adult: Case Report-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF HEAD NECK & SPINE SURGERY

Abstract

Traumatic leptomeningeal cysts are a rare

complication of a childhood skull fracture. Clinical manifestations of a

childhood trauma are very rare in adults and usually presents as a

nontender subcutaneous mass with progressive neurological deficit and

seizures.

Keywords: Leptomeningeal cyst; Adult; Trauma; Seizures; Skull fracture

Abbrevations:

CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CSF:

Cerebrospinal Fluid; T1WI: T1-Weighted Images; T2WI: T2-Weighted Images

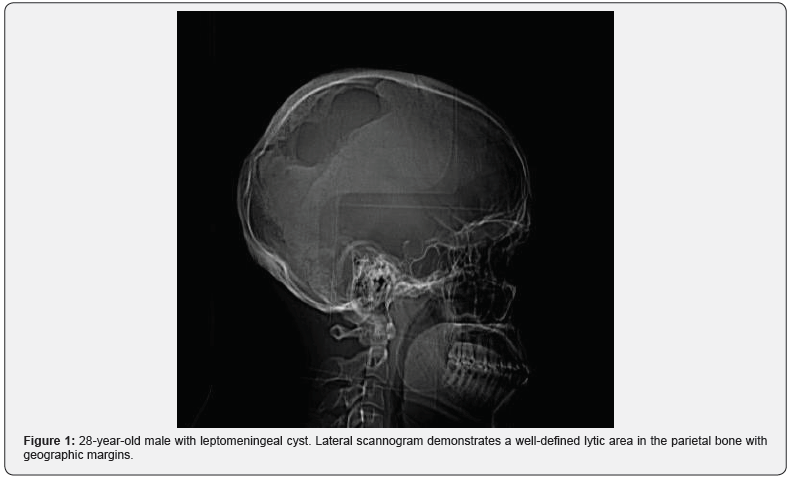

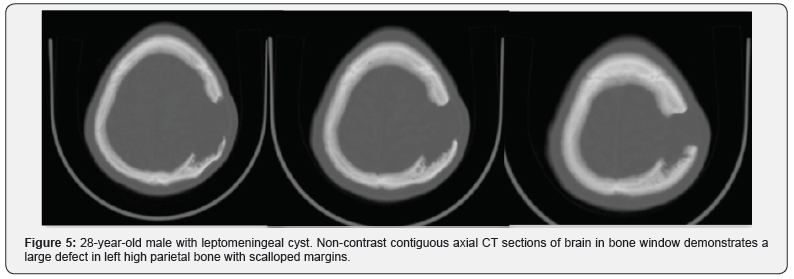

A 28-year-old male presenting with a gradually

increasing scalp swelling in the left parietal region over a long period

and seizures. The patient was conscious. On physical examination,

there was a cystic swelling over the left parietal prominence. The

swelling was compressible but non-tender and non-pulsatile. There was a

history of head injury during infancy (Figure 1-5).

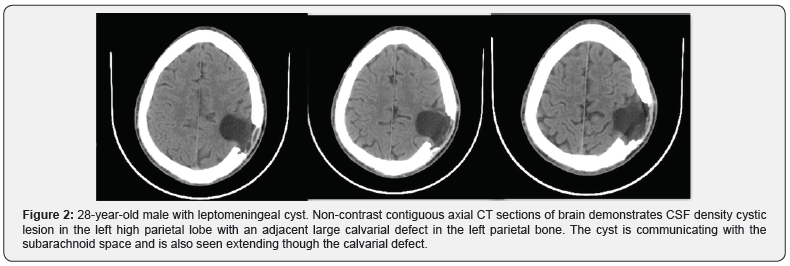

A non-contrast enhanced head computed tomography (CT)

examination was performed on a multidetector CT (Lightspeed

ultra, GE Medical Systems) and demonstrated a large calvarial

defect in the left parietal region with irregular and beveled margins.

An adjacent CSF density cystic lesion of size 42x41mm noted

in the left high parietal lobe. The cyst was seen communicating

with the subarachnoid space and also seen extending though the

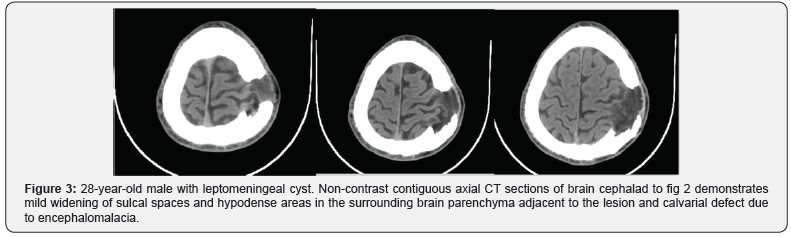

calvarial defect. Mild widening of sulcal spaces and hypodense

areas also noted in the surrounding brain parenchyma due to

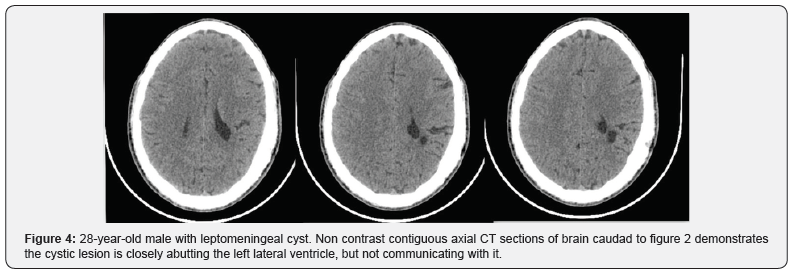

encephalomalacia. The cystic lesion was seen closely abutting the

left lateral ventricle with focal dilatation of the ventricle. But there

was no communication of the cyst with the ventricle. Corrective

surgery was done. The intraoperative and postoperative period

was uneventful.

Growing skull fractures usually occur due to severe head

trauma during the first three years of life, particularly in infancy.

Incidence reported is only.05 to.1% of skull fracture in childhood

[1,2]. Cause for growing skull fractures is multifactorial but the

main factor is tear in the dura mater. The pulsatile force of CSF

and pressure of growing brain will cause cerebral or subarachnoid

herniation through the dural tear which causes the fracture in

the thin skull to enlarge. This interposition of tissue prevents

osteoblasts from migrating, inhibiting fracture healing. The

resorption of the adjacent bone by the continuous pressure from

tissue herniation through the bone gap adds to the progression of

the fracture line (Tables 1-2). Table abbreviations: CT = Computed Tomography, MRI =

Magnetic Resonance Imaging, CSF = Cerebrospinal fluid, T1WI= T1-weighted

images,

T2WI= T2-weighted images. Table abbreviations: CT = Computed Tomography, MRI =

Magnetic Resonance Imaging, CSF = Cerebrospinal fluid, T1WI= T1-weighted

images,

T2WI= T2-weighted images.

The brain extrusion may be present shortly after diastatic

linear fracture in neonates and young infants [3] resulting in focal

dilatation of the lateral ventricle near the growing fracture. This

focal dilatation may be seen in adults which is also seen in this

case. This focal dilatation is reversible and may normalize after

surgical repair [4]. Cranial defects never increase if the underlying

dura is intact. Leptomeningeal cyst never occurs if the dura is

intact.

Another risk factor is severity of underlying trauma. A linear

fracture associated with hemorrhagic contusion of subjacent brain

suggests a trauma significant enough to cause dural laceration.

Cystic changes at the growing fracture site may be because of

cystic encephalomalacia. Post traumatic aneurysms and subdural

hematomas have also been reported to accompany growing skull

fractures [6,7]. Though most patients show damage to underlying

brain, this finding is not a prerequisite for the development of

growing skull fractures [8].

These skull fractures after reaching maximum extent will

cease to grow and remain stable throughout adulthood [2,5].

A depressed fracture usually does not become a growing

fracture [9] but a linear fracture extending from a depressed one

can become one [10].

A fracture with a diastasis of >4mm may be considered at

risk of developing a growing skull fracture [3,11,12]. But a post

traumatic diastasis of a cranial suture is an unusual site for a

growing fracture. Growing fractures can even be seen in usually

in linear fractures in thin areas of skull base associated with dural

laceration, for e.g.: Orbital roof, ethmoid plate, frontal sinus.

These fractures commonly present as a progressive, scalp

mass that appears sometime after head trauma sustained during

infancy. There may seizures and hemiparesis, but an asymptomatic

palpable mass may be the sole sign. The usual site is the parietal

region. A growing fracture at the skull base may present with

ocular proptosis or CSF rhinorrhea or otorrhea.

A plain radiograph may show a fracture line that crosses a

coronal or lambdoid suture, but it is usually limited to a parietal

bone [13]. CT or MRI demonstrates a cystic lesion near the fracture

site communicating with the subarachnoid spaces and extending

though the bony defect. Margins of bony defect may be beveled

or irregular. Adjacent brain parenchyma usually shows mild

encephalomalacia changes and focal atrophy. Gliosis may also see

in the adjacent brain parenchyma. On CT scan gliosis is seen as

hypodense areas. On MRI gliosis is seen as hypointense T1 and

hyperintense T2 signals.

Because of neurological deterioration and of seizure disorder

surgical correction of growing fractures is recommended.

Even though traumatic leptomeningeal cyst is rare in adults, it

should be considered in the differential diagnosis of intracranial

cystic lesions with adjacent calvarial defects.

To know more about Open Access Journal of

Head Neck & Spine Surgery please click on:

To know more about juniper publishers: https://juniperpublishers.business.site/

Comments

Post a Comment