Dysphagia: Approach to Assessment and Treatment-Juniper publishers

Juniper publishers-Journal of Head Neck

Dysphagia is a medical term used to describe a

swallowing disorder. It may refer to a swallowing disorder involving any

one of the 3 stages of swallowing: oral, pharyngeal, esophageal. It is

not a primary medical diagnosis, but a symptom of a disease, &

therefore is described most often by its clinical characteristics.

Dysphagia is delay in or misdirection of a fluid or solid bolus as it

moves from mouth to the stomach. Delay in or misdirection of the food

bolus may interfere with functional oral intake.

The nature of dysphagia

Aspiration occurs whenever food enters the airway

below the true vocal folds. Aspiration can occur before, during, or

after the swallow.

Aspiration before the swallow

Aspiration occurs before the swallow in the case of a

delayed or absent swallow initiation. It may also be the result of poor

tongue control, which allows food to trickle into the pharynx while the

patient is still chewing. Apparently, a “neurological override” exists

which prevents the initiation of the swallow while one is still chewing

[1].

Aspiration during the swallow

Aspiration occurs during the swallow when the vocal

folds fail to adduct or the larynx fails to elevate. (Remember that this

type of dysphagia is uncommon. Only 5% of dysphagias involve problems

with airway closure).

Aspiration after the swallow

Aspiration can occur after the swallow in several

different circumstances: The patient may pocket food in the oral cavity.

Later, when he or she lies down to sleep, the food will fall down into

the airway. Food may get stuck in the pharyngeal recesses. This happens

to everyone, but someone with a normal system would realize that the

food was there and swallow again. A CVA or TBI patient may have a

sensory impairment and allow the food to drop into the larynx. Due to

reduced laryngeal elevation, food may remain on top of the larynx

(Logemann, 1989).

Signs & symptoms of dysphagia

Early identification and treatment (Tx) may help

avoid adverse medical complications such as under nutrition or

respiratory infection. Because a variety of medical specialists can be

involved in the care of the patient with dysphagia, all must be capable

of detecting the signs & symptoms characteristics of dysphagia. Some

symptoms may be overt, such as those in the patient who coughs while

eating, where as others may not be overt, such as those in the patient

who may not have a swallowing complaint but comes to the swallowing

specialist with a history of unexplained pneumonia.

A radiographic evaluation of swallowing may reveal

that food or fluid is silently entering the air way during swallow,

resulting in aspiration.

Symptoms of dysphagia: symptoms are

usually are defined as any perceptible change in bodily function that

the patient notices. This change eventually leads the patient to seek

medical help when it causes pain or discomfort or negatively impacts

his/her life style. Some people have adverse medical symptoms &

ignore them until the severity of their problem significantly affects

their physiologic or mental health. Others seek immediate medical

attention. Both groups may be diagnosed with a disorder that is similar

in type & severity.

Patient description: the physical examination of a

patient with dysphagia may begin by asking him or her to describe the

symptoms. Because dysphagia often is secondary to neurological disease

that also may compromise communication skills, not all patients can

provide a report of their symptoms.

Because of cortical deficits, others may give

unreliable or scant information. They make changes in their eating

habits to accommodate their symptoms, such as chewing food more finely

or eliminating troublesome items from their menu. Others know that they

are having difficulty swallowing but have a difficult time describing

the specifics of their symptoms. Often it is difficult for them to

remember how long those symptoms have been apparent.

This may be due to the inherent flexibility of the swallowing

tract to accommodate changes in function. For patients who are

able to communicate symptoms of their dysphagia, a detailed

description may be useful in helping establish a diagnosis.

Detailed descriptions also may be used to help the examiner

focus on the types of diagnostic tests that may be most useful in

delineating the source of the patient’s complaint. Some clinicians

find it useful to explore a patient’s dysphagic symptoms by

questionnaire. This method may help ensure that all relevant

questions relating to the patient’s symptoms are addressed by

the examiner. It also gives the patient a chance to think carefully

about his/her symptoms before responding.

Obstruction: one of the common complaints from dysphagic

patients is that food or fluids “gets stuck”. Most often, they

report that the sticking sensation is in the throat or esophagus.

Some patients do not use the word stuck but may use the word

“fullness”. When they localize the feeling of obstruction to the

throat, they often describe their complaints as “a lump in the

throat” when eating.

The medical term for this feeling is globus. Some physicians

have used the term globus hystericus to describe this sensation,

because it was once thought usually that the description of lump

in the throat usually was associated not with organicity, but with

symptoms of hysteria.

Liquids vs solids: Patient may report a change in their

dietary habits that is associated with perceived dysphagia.

Those who complain of the globus sensation often have more

difficulty swallowing solids than liquids. Patients with solid food

dysphagia are more likely to have disorders of esophageal origin;

whereas these who complain of dysphagia for liquids are more

likely to have oropharyngeal dysphagia. When patients complain

of choking on liquids or solids, a more pharyngeal focused cause

is suggested. Whereas those who report dysphagia for liquids &

solids without choking episodes may have a more esophageal

focused cause.

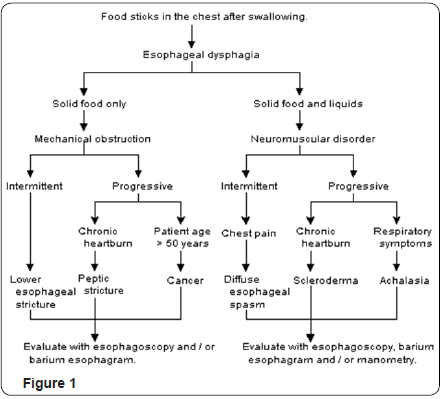

Gastroenterologists who support the esophagus as the source

of dysphagia may use a decision tree such as the one presented

below to assist in diagnosis. Such a decision tree has not been

validated against a large number of patients with confirmed

diagnosis; however, the concept is useful because the symptoms

related to the represented diseases are well known, & the no. of

potential causes for esophageal dysphagia is limited.

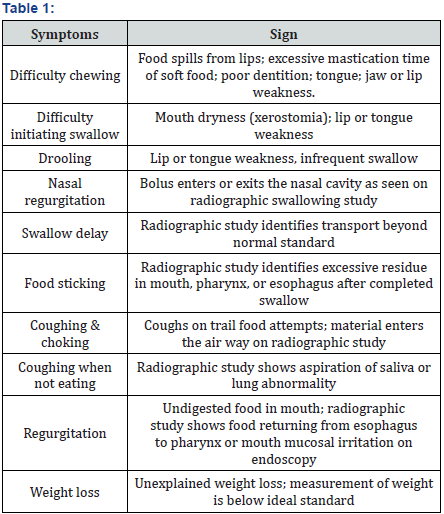

Symptoms & signs that may related to many disease entities.

Thus using a decision tree approach based on patient complaints

does not provide enough precision to help the clinician establish

a diagnosis for Patient with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastro

esophageal reflux: some Patient complain of episodes of gastro

esophageal reflux (heart burn) associated with their complaint

of dysphagia. Some Patient describe pain or fullness in the chest

associated with their reflux.

Others may have reflux & dysphagia but may be unaware that

they have reflux because the overt symptoms of chest pain or acid

taste are not present. Not all Patients describe episodes of reflux

unless questioned by the examiner, because they may not relate

their episodes to their dysphagia. This is particularly true when

Patient complain of globus sensation in the neck, because they

might think that reflux in the esophagus could not be related to a

problem in the throat. Eating habits: a Patient’s report of changes

in his/her eating habits may signal the presence of dysphagia, its

level of severity, & its psychological impact.

Complaints that elimination of specific food items from the

diet, such as liquids or solids or items that are sticky or crumby,

may help the examiner focus the evaluation. Excessive chewing

of solid food to avoid a sticking sensation may be more consistent

with esophageal disease Vs the pharyngeal focused complaint

that liquids always seem to come back through the nose. People/

patients who report excessive time to finish a meal often have

dysphagia that requires careful evaluation. Patients who report

that they no longer feel comfortable eating in a restaurant

because they have to regurgitate or choke should be examined

with care. Patient who have experienced marked weight loss

or who no longer enjoy the pleasures of eating probably have

dysphagia that has reached a high level of severity.

Signs of dysphagia: signs are objective measurements or

observations of behaviors that people elicit during a physical

examination. In a dysphagic patient who is cooperative, this

measurement entails an examination of the cranial nerves

relevant to swallowing. Some signs are seen during observation

of the Patient eating. Signs & symptoms may overlap. Example

A Patient may complains have liquid going into the nose &

food sticking. Both may be seen by the examiner on the video

fluoroscopic swallowing study.

- The physical evaluation of a Patient may reveal signs that are consistent with dysphagia, such as

- Drooling from the lip or tongue weakness

- Poor dentition

- Loss of strength or range of motion in the tongue, jaw or velum

- Poor strength or coordination may result in choking on liquids during test swallows or in lack of bolus flow

- The pt’s cognitive status may impact swallowing eg. Failure to chew, talking while swallowing, inattention to the feeding process

Patient who are hospitalized may have more overt medical

signs, such as

- Feeding tubes that are already placed

- A tracheostomy tube

- Poor dentition

- Respiratory congestion after eating

- Requirement of excessive oral & pharyngeal suctioning

- Eating refusals

- Under nutrition & muscle wasting

- Inability to maintain an upright feeding position

- An endo tracheal tube

- Regurgitation of food

The process of evaluation begins with case history, clinical or

bedside swallow examination and the instrumental examination.

In many assessment protocols, the case history and bedside

swallow evaluation are combined. They provide greatest

amount of information on the patients eating behavior, language,

cognition and oromotor function.

Screening procedure

Screening procedures provide the clinician with some

indirect evidence that the patient has a swallowing disorder. It

tend to identify the signs and symptoms of dysphagia such as

coughing behaviors, history of pneumonia, drooling, chewing

difficulties or the presence of residual food in the mouth.

Screening procedures are generally performed at the patient’s

bedside or in a home or school environment and provide the

clinician with increased evidence that the patient needs an in

depth physiological assessment.

Screening procedures provide the clinician with some

indirect evidence that the patient has a swallowing disorder. It

tend to identify the signs and symptoms of dysphagia such as

coughing behaviors, history of pneumonia, drooling, chewing

difficulties or the presence of residual food in the mouth.

Screening procedures are generally performed at the patient’s

bedside or in a home or school environment and provide the

clinician with increased evidence that the patient needs an in

depth physiological assessment.

In adults, the Burbe Dysphagia Screening Test (BDST) is used

which consisted of a seven items. It checks the presence of one

or more items in the test results in failure and then referral for

a complete bedside swallow evaluation. The screening items are

- Bilateral strobe

- Brain stem stroke

- History of pneumonia in acute phase strobe

- Cough during 303 water swallow or associated with feeding

- Failure to consume one half of meals

- Prolonged time required for feeding

- Non-oral feeding programs.

This test is reported to highly valuable in identifying patients

are risk for swallowing problems

Bedside examination

It is designed to define the function of patients lip, tongue,velopharyngeal region, pharyngeal walls and larynx as well as

his/her awareness of sensory stimulation. The physiology of

some of these structures can be easily assessed at the bedside,

while others can only be examined accurately in radiographic or

other instrumental study. It consists of following examination.

Review of patient’s medical chart

- Prior to entering the patients room, the clinician should carefully review the patients medical chart, focusing particularly on the medical diagnosis, any prior or recent medical history of surgical procedures, trauma, neurological damage as well as patients current medications.

- After defining medical diagnosis, the clinician should immediately consider what physiologic or anatomical swallow disorders that are typical of that diagnoses.

- History of any respiratory problems should also be identified, including need for mechanical ventilation or tracheostomy tube, the conditions under which they were placed (emergency/planned).

- Prior history of GI dysfunction should be noted.

- Prior history of dysphagia from earlier stroke or head injury should be high-lightened even if the patients or his/ her family indicates that the patient returned to oral intake with no apparent difficulty.

- Medical chart should reveal the patients current nutritional status and the presence of any non-oral nutritional support such as naso-gastric tube.

- Clinical should also be able to identify the patients general progress as well as prognosis from chart review.

Oromotor examination

It begins with the examination of anatomic structure of oral

cavity including its symmetry and presence of any scar tissue

indicating surgical/traumatic damage. The oral examination

should note the presence and status of oral secretions, especially

the pooling of secretions or excessive dried secretions. In general,

the locus of excess secretions in the oral cavity indicates the

areas of lesser lingual control or injury. Oromotor examination

should then proceed to examination of strength, range of motion

and coordination of the lips, tongue and palate for speech and

non-speech tasks as well as observation of lingual function and

lip closure while the patient produces spontaneous swallows,

clinician notes down the frequency of spontaneous swallows.

Respiratory support

Respiratory support should be defined by counting the rate

of breaths per minute. Patients should be asked to hold their

breath for a total of 1 sec, then 3, 5 and 10sec and the clinician

should observe whether this behavior creates any respiratory

distress. Duration of breath hold should be increased as tolerated

by the patient. This determines whether the patient can tolerate swallow maneuvers or other therapy procedures that increase

the duration of apneic or airway closed period during the

swallow. Generally patients need to hold the breath of 5 seconds

to use swallow manneurs comfortably. The patients coordination

of swallowing and respiration should be observed.

Prolonged phonation

Prolonged phonation on the vowel/o/ should also be

examined in terms of both vocal quality and respiratory control

used. Clinician should then check whether the patient is able

to take an easy inhalation followed by a slow drop of chest and

inward motion of abdomen to produce a prolonged vowel on

sustained phonation of at least 10 seconds.

Gag reflex

This is to examine the pharyngeal wall motion as part of

the motor response for gag. The pharyngeal wall motion during

the gag should be symmetrical. Any asymmetry-unilateral

pharyngeal wall paresis.

Laryngeal examination

- Series of voluntary tasks will be tested which are as follows:

- Vocal quality on prolonged /a/ (hoarse, gurgley)

- Strength of voluntary cough

- Strength of throat clearing

- Clarity of /h/ and /a/ during repetitive /ha/

- Pitch range (slide up and down scale)

- Loudness range

Cognitive and language characteristics: Through all

oromotor testing, the clinician will be examining the patients

general behavioral level, ability to discipline his/her own

behaviour, and focus on tasks, impulsiveness, ability to respond

to commands, etc, should also be tested.

Optimal protocols: De Pippo et al. have proposed other

options in place of bedside swallow evaluation. They found that

cough or voice change during or directly after drinking 303

of water was sensitive and valid screening tool for aspiration

following a stroke. It should be remembered that the clinical

swallow assessment with water should be tried only after the

findings from patient history and oropharyngeal examination

should be taken into account. Patients unable to tolerate their

secretions, who have limited attention such as those after a

severe stroke or who resist for some other reason may not be the

candidates for clinical swallow test.

Dysphagia screening: Prior to

bedside swallow, use of

dysphagia screening test may be appropriate. This is usually

done by speech language pathologist but may also be done by

a nurse trained in the procedure. Two such screening tests are

the Burbe Dysphagia Screening Test (BDST) and the screening

test proposed by Odderson & McKenna. The BDST consists of a seven

item test. Presence of one or more items in the test results

in failure and then referral for a complete bedside swallow

evaluation.

The screening items are

- Bilateral strobe

- Brain stem stroke

- History of pneumonia in acute phase strobe

- Cough during 303 water swallow or associated with feeding

- Failure to consume one half of meals

- Prolonged time required for feeding

- Non-oral feeding programs.

These 2 tests are reported to highly valuable in identifying

patients are risk for swallowing problems.

Dye test

Also known as Blue dye test may be used to determine the

presence of aspiration in a tracheostomized patient. A few drops

of methylene blue or vegetable coloring are placed in the mouth,

tracheostomy cuff is deflated, and the tracheostomy tube is deep

suctioned for secretions that may have been resting on or above

level of cuff. The patients tracheostomy tube is deep suctioned

and looking for evidence of dyed material in airway. This may not

detect trace amounts of aspirated materials.

Auscultation: Chest and cervical

Placing a stethoscope over various parts of airway provide

indirect evidence of aspiration. Through this, he can listen to

airflow during normal breathing, swallow sound. It determines

whether other tests are needed.

Clinical Swallowing Examination (CSE)

The clinical swallowing examination allows a circumscribed

exploration of patients muscle function, sensation and airway

protective functions. This CSE allows the clinician to develop

management program for the patient and to determine the

necessity of further instrumental assessment. The clinical

swallowing examination protocol includes the following:

CSE 1 Mental status

We know that there is interdependence between safe swallow

function and cognitive and behavioral factors such as attention,

memory, judgement, reasoning, orientation and sequencing

skill. In patients with head injuries, the frequency of swallowing

disorders was found to decrease as patient’s scores on level of

cognitive function scale improved [2].

During the interview, clinician should be vigilant for

indications of reduced mental function.

- Are the clothes clean or blotched with food particle? (Subtle questions)

- Is there an evidence of appropriate attention to cleanliness and hygiene? (Subtle questions to cleanliness and hygiene? (Subtle questions).

- Is the individual attending to the questions and answering appropriately?

- Is there a drift during the session?

- Is the caretaker/spouse acting as a surrogate in the interview without invitation…… etc

Many scales have been developed for measuring and

monitoring mental status eg.

a. Glassgow coma scale. It is scored for 3 behaviors, eye

opening verbal response and motor response. The score

range from 3 (severe coma) to 15 (full awareness)

b. The Ranchos Losnmigos scale.

c. All these scales tell us about degree of cognitive

impairment.

CSE 2 Speech/Articulation

Here the clinician makes a gross determination of

a) Precision of articulation i.e. speech intelligibility, look

for the % speech intelligible

100% - normal

>50% - moderate

35 – 50% - severely affected

< 35% - very unintelligible

b) Rate – normal; slow; accelerated

c) Predominant error- Check whether distortion/

omission/substitutions present. Distortions are more likely

to be present in neurogenic speech disorders.

CSE 3: Respiratory function

Here the respiratory subsystem is assessed which includes –

a) Volitional cough: Ask the patient to take a breath and

produce as great a cough as possible. Check whether he is

able to cough or not if not see for the presence of forced

expiration, throat clearing or hawking. (Hawking: audible

effort to force out the phlegm from throat).

Also check for productive cough (transport of material from

lower airways.

Check for loudness (normal, weak/audible or very weak/

inaudible).

b) Sustained expression while counting: Ask the patient to

inhale as deeply as possible and with a single breath, count

as high as you can. The score is derived from the number

reached when patient counts aloud on a single exhalation

after maximum inspiratory effort.

c) Index of pulmonary dysfunction: Smeltzer, Skurnick,

Toroiano, Cook, Duran and Lavietes (1992) employed an index sensitive to pulmonary dysfunction. The possible

range of scores 4 (normal maximal expiratory pressure to11

(poor maximal expiratory pressure) [3,4].

CSE 4: Voice/resonance

For assessing this, clinician will rely on connected speech

and check for normal/hoarse/ harsh/hypophonic/ aphonic or

wet dysphonic/hypernasal.

CSE 5: Position

Clinician will observe the patients habitual body and head

position and examine the patients adaptations or apparatus

used to assist in support. The clinician then will attempt to elicit

alterations in body and head positions.

Body position- Leaning with self support.

- Supported by apparatus.

- Reclined.

- Flexion.

- Extension.

- Head turned to left/right

Eliciting changes in position during the clinical examination

allows the examiner to probe for the patients capacity to

change the position or posture later in assessment process.

Repositioning the head and trunk has been shown to cause

changes in biomechanics of swallowing.

CSE 6: Lip sensation/strength/seal

a. Ask the patient to close his/her eyes and respond

either verbally or by raising a finger or hand in response to

stimulus placed on the lip and its marging (light momentary

brush over).

b. Checking drooling is present/not.

c. Note down the habitual oral position ie open/closed.

d. Lip strength can be assessed by asking the subject to

purse his/her lips with as much pressure as possible and ask

him to lift the upper and lower lip with tongue blade along its

entire length.

CSE 7: Mouth opening

a. The patient is asked to open his mouth as widely as

it will open and see whether it is normal/reduced mouth

opening (approximate mouth opening: 1 cm).

b. This is assessed because patients with small mouth

openings may have great difficulty placing even small volumes of food in their mouth. The amount of time and

effort need to take in enough food to maintain nutrition lead

these patients to abandon oral solid foods in favour of liquid

diets that are easily consumed by straw.

CSE 8: Muscles of mastication

Masseter and temporalis: They act to move the mandible to

a closing position. With the jaw muscles relaxed, ask the patient

to clench down on a tongue, blade placed along the length of the

molars on the right or left side of oral cavity. Palpate and note

down the bulging and firmness.

Lateral and medial pterygoid: Check for protrusion and

lateralization by applying resistive pressure on the other side

with other hand.

Check for pain while performing the above mentioned tasks,

see whether the pain is unilateral or bilateral also.

CSE 9: Dentition and periodontum

Clinician assesses the patients dentition prosthetic dentition

and gingiva. The equipment needed includes a penlight, gloves

and tongue depressor – we have to make a note of existing teeth

and missing teeth in the tooth chart - also indicate the condition

of existing dentition.

Removable prosthetics: While inspecting the mouth, make

note of removable partial/complete dentures. A partial denture

replaces one or more teeth in one arch. A complete denture

replaces most or all of the teeth in an arch. Indicate where the

prothesis are in place and note their condition with the patients

mouth wide open, grasp the denture and tug on it to determine

firmness – check for the presence of food particulate or plague

on the surface of the denture.

CSE 10: Salivary flow/appearance of oral mucosa

Check whether the salivary flow is normal or any

hyposalivation is present.

Check for the appearance of oral mucosa i.e. surface of the

tongue appears severely dry, tongue with cracks and fissures etc.

CSE 11: Oral/pharyngeal gag

Have the patient open his/her mouth as you probe the

surface of the tongue, faucial pillars and posterior pharyngeal

wall. Initially apply light touch and probe for the response. If no

response, apply enough pressure.

CSE 12: Tongue movement/strength

- Request the patient to open his/her mouth and observe the tongue at rest and during protrusion. Check whether the tongue is normal/atrophied/deviated/dyskinesia.

- Also check for nasal respiration. thro lips. This task tests the posterior seat of oral cavity.

- Tongue strength should be tested with isometric exercises. See whether strength is normal/reduced.

- Tongue range of motion can be checked by requesting the patient to move the tongue tip along the entire length of maxillary and mandibular buccal sulci. Also ask the patient to stroke over the surface of hard palate.

CSE 13: Velar elevation

Ask the patient to say or yawn and check for velar elevation.

CSE 14: Volitional swallows/laryngeal elevation

- Place the ring, middle and index fingers along the entire surface of throat with the index finger in the superior position. Situate your finger so that the thyroid notch is nestled between ring and middle fingers. Here index fingers should be resting on suprahyoid muscles. Request the patient to swallow with the fingers lightly resting upon the suprahyoid muscles. There may be a moment of delay as the patient collects saliva within oral cavity and prepared to swallow.

- Patients with xerostomia – no enough saliva to initiate dry swallows.

- Apraxia – no coordinated swallow

- Cognitive impairment – unable to swallow on common.

- The sublingual musculature pull away from index finger as the suprahyoid muscles contract. During elevation, the thyroid notch should move to a point above the middle finger and at the apex of the swallow, may come in contact with the inferior margin of the index finger. A swallow following this pattern is normal.

CSE 15: Food and liquid swallows

The clinician will elicit swallows by presenting food and

liquid of varying volumes and consistencies to the patient. The

clinician will observe and record signs and symptoms that are

exposed during the session. As a basic guideline, the clinician

should hold safety as the highest priority. Clinician should be

sure of the following:

- Alertness

- Cough: strong cough, weak cough

- Accordingly we can introduce any material in the patients mouth.

- Order of presentation should be taken into account. The initial delivery should be of and consistency that will be the easiest for the patient to consume. Graded activities should be done eg. Slowly increasing the volume.

- Enter the maximum amount of food or liquid presented with a particular material (listing the volume is also important).

- Timing of the onset is dependent on the materials presented with longer period necessary as the hardness of the food increases. The elapsed time should begin as the food enters the mouth and end as the larynx elevates for pharyngeal swallow.

- Clinician should count the number of swallows per bolus delivery by recording the number of elevations of the larynx. When multiple swallow occurs, the clinician should query the patient regarding the presence of food sticking. If able, have the patient point to the perceived location of the residue. Accordingly instrumental techniques is indicated.

- Oral signs: Clinicians should look inside the patients oral cavity following each food presentation in those patients who report oral stage difficulties. Attention should be given to all cervices and pockets where food can get accumulated.

- Airway signs – note the presence of wet dysphonia and frequent cough (liming and strength).

Instrumental Techniques for the Study of Swallowing

Introduction

A number of imaging and non-imaging instrumentation

procedures have been used to study various aspects of normal

and/or abnormal swallow physiology. Each procedure provides

some pieces of information on oropharyngeal anatomy or

swallow physiology. It is important that the clinician be

familiar with the types of information, each procedure provides

information about swallowing and basic methodology for each

procedure. These instrumental procedures include

- Imaging studies.

- Non-imaging studies.

Imaging studies

Several technologies can be used to image the oropharyngeal

region which include ultra sound, video endoscopy, video

fluroscopy, pulse oximetry, scintigraphy, CT and MRT,

esophagoscopy/gastroscopy.

Ultra sound

Ultra sound uses high frequencies sounds (>2MHz) from a

transducer held or flexed in contact with skin to obtain a dynamic

image of soft tissues. As ultrasound does not penetrate bone, its

use is limited to the soft tissues of oral cavity and parts of the

oropharynx. Here a handheld transducer is placed submentally

and is rotated 90 degrees. It is used to observe tongue function

and to measure oral transit times as well as motion of hyoid

bone. Real food can be used here.

Videoendoscopy (FEES)

It has been used increasingly in recent years to examine the

anatomy of oral cavity and pharynx and to examine the pharynx

and lx before and after swallowing. First described by Langmore

et al. It requires the passage of a fiberoptic laryngoscope into nares, over the velum to a position above the epiglottis. After

placing the endoscope, examiner notes the anatomic structures

and observes the functions of the velum, epiglottis and larynx

using sustained phonation or repeating coca cola. Trial dry

swallows are prompted to elicit laryngeal elevation.

Specific amounts of liquids and food consistencies treated

with food dye are viewed as they pass the pharynx and larynx.

During the time of airway closure, swallow cannot be visualized

as the pharyngeal walls contract over the bolus, collapsing the

lumen over the endoscope (whiteout phase). Monitoring of the

bolus is only possible before and after pharyngeal swallow.

Video camera monitors the bolus as it enters the view from oral

cavity to pharynx.

It can be used to determine sensory dysfunction in dysphagic

patients. To perform the test, an air pulse generator is used

to send a pulse of air through a port in a specially designed

flexible nasopharyngoscope. Air pulses can be delivered to the

supraglottic larynx and pharynx areas. Using a calibrated puffs

of air, sensory thresholds can be determined using one of the

psychophysical testing methods. The twitching response of the

mucosa suggests the sensory awareness of stimulus.

Scintigraphy

It is a nuclear medicine test in which the patient swallows

measured amount of radioactive substance (technetium-99m)

combined with liquid/food. A special gamma camera records

images of the organs of interest over time. This can also be

used to identify aspiration, quantify aspiration over short/long

periods of time. It can also be used to calculate transit time and

residual pooling of a bolus before and after treatment. If there is

no aspiration and reflux is suspected, the patient is rescanned

every 15-20 min for several hours to detect reflux.

Pulse oximetry

A relatively new approach to monitor swallowing and

possibly detecting aspiration is pulse oximetry. It is based on

the principle that reduced and oxygenated hemoglobin exhibit

different absorption characteristics to red and infrared light

emitted from a finger/ear probe. Pulse oximetry measures

oxygen desaturation of arterial blood, a condition which is

thought to occur as a result of aspiration. It is non-invasive,

simple may be repeated often but does not provide diagnostic

information to formulate treatment plans. It offers information

regarding presence and possibly severity of aspiration.

Videofluroscopy

Because swallow is a dynamic and rapid process,

videofluroscopy is particularly well suited to the study of this

physiologic function. The term cookie swallow has been in the

past but this does not describe the procedure adequately.

Modified barium swallow has two purposes: To define

the

abnormalities in anatomy and physiology causing the patients

symptoms. To identify and evaluate treatment strategies that may

immediately enable the patient to eat safely. Baruim swallow test

can be used to examine oral transit times, structural competence

of oesophagus, particularly lower two thirds of oesophagus very

well.

Test

Under fluoroscopic observation, controlled by the radiologist,

the patient ingests barium coated boluses or liquid barium of

varying consistencies.

Placement of food in the patients mouth: Generally food

is placed in the patients mouth on a disposable plastic spoon.

If a patient has a bite reflex, a heavier plastic spoon is more

appropriate. For infants, bottle and nipple may be used.

Type and amount of material used: At least three

consistencies of material are used in the modified barium

swallow to investigate patient complaints of variable swallowing

ability. Thin liquid barium (as close to water as possible), barium

paste (chocolate pudding mixed with esophatrast) and the

material requiring mastication (a cookie coated with pudding

mixed with esophatrast). At least two swallows of each material

are given in following amounts: 1ml 3ml, 5ml, 10ml and cup

drinking of thin liquid; 1/3 teaspoon of pudding and a fourth of

a small Lorna Roone Cookie coated with barium [2]. Volume of

liquid is increased until or unless patient aspirates.

Positioning the patient: Often the most difficult and time

consuming part. No. of chairs for positioning patients during the

radiographic study have been designed. A patient who is mobile

and able to sit without a backrest can be seated on the horizontal

platform attached to fluoroscope table and raised/lowered to

desired height. Most machines are fitted with handles so that

the patient can stabilize his/her position. Some fluoroscopy

machines will not accommodate wheel chairpersons or persons

on cart. If permitted, they are positioned on a cart with the head

of cart elevated to at least 90 angle.

Focus of fluoroscopic image: The fluoroscopy tube should

focus on lips anteriorly, hard palate superiorly posterior

pharyngeal wall posteriorly and the bifurcation of the airways

and oesophagus inferiorly. Many fluoroscopy machines permit

image magnification.

Measures and observations to be made: lateral view:

This permits a number of measures and observations critical to

the identification of patients anatomic/physiologic swallowing

disorder. It helps in measuring oral, pharyngeal and oesophageal

transit time. This permits identification of the location of the

bolus as it moves along upper aerodigestive tract from anterior

superior to posterior inferior. It permits the analysis of patterns

of lingual movement, estimate of amount of material aspirated

per bolus, as well as the reason for aspiration. The timing of

aspiration relative to triggering of pharyngeal swallow is also

best examined.

The eight step scale maybe quite useful to monitor changes in a patients ability to control aspiration material.

- Does not enter airway

- Remains above folds / ejected from air way

- Remains above folds / not from air way

- Contact folds / ejected from air way

- Contact folds / not ejected from air way

- Pass below folds /ejected into lx or out of air way

- Passes below folds /not ejected despite effort

- Passes below folds / no spontaneous effort to eject.

Posterior anterior view (P-A view): P-A view is helpful in

looking at asymmetries in function, particularly of pharyngeal

walls and vocal folds and in viewing the residual material in the

valleculae and in one or both pyriform sinuses. It provides vocal

fold movement picture too.

Other radiographic tests for dysphagia

Upper gastro intestinal series: The single contrast

esophagram study fills and distends the lumen with thin liquid

barium. Intrinsic mural irregularities and masses and extrinsic

impressions are visible. An air contrast study provides the same

information but allows a more detailed view of mucosa. For an air

contrast barium study, the patient ingests effervescent crystals

followed by thick barium. A barium swallow has both dynamic

and static components. The dynamic portion, fluoroscopy can be

recorded on tape (video fluoroscopy cine radiography) for later

review. The static portion is recorded on a series of rapid still

frames.

The barium swallow can identify intrinsic and extrinsic

pathology. Intrinsic abnormalities include tumors,

cricopharyngeal dysfunction, aspiration of barium into airway

or reflux into nasopharynx, diverticulas webs and esophageal

dysmotility. Extrinsic masses such as cervical osteophytes and an

enlarged thyroid gland maybe visualized directly or suspected

by their effect on the barium column.

The subjective location of dysphagia does not always

correspond to anatomic location of pathology. Therefore, the

barium study when used to evaluate dysphagia should extend as

low as the gastric fundus or cardia. The upper gastroesophageal

series evaluates the stomach and relaed areas. Obstruction or

dysfunction of these areas may cause or contribute to esophageal

dysfunction (eg. GERD). Thus the transitional barium swallow

evaluates the upper aerodigestive tract between oral cavity or

oropharynx and gastric fundus or cardia. It is not intended to

identify swallow dysfunction or to dictate treatment as in the

modified barium swallow.

Computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging:

They are used to delineate the anatomy of a particular region of

the head, neck or other components of the upper aerodigesture

tract. The most common use is to identify a site of lesion such as cerebrovascular accident within the central nervous system or

to delineate the extent of an intra/extra luminal space occupying

system. In general, CT offers direct axial and coronal images that

better define bony anatomy.

MRI better delineates the soft tissue in saggital, coronal

and axial planes but takes longer to complete the images and

thus is prone to motion artifact. High speed MRI such as fast

low angle shot (FAST) or echo planar imaging, has allowed a

dynamic analysis of the pharyngeal phase of swallowing that

was impossible with conventional MRI. The pharyngeal oral

cavity, laryngeal lumen and musculature can be evaluated during

motion, allowing the assessment of swallowing mechanism.

During FAST MRI, images are obtained as a bolus containing

contrast substance is so allowed. Here temporal and spatial

resolution is poor, but no exposure to radiation.

Non imaging techniques: They provide a variety of types

of information about swallowing but do not results in pictures

of the swallowing process or the food being swallowed. Instead,

most result in amplitude over time displays of the swallow

parameters being examined.

Electromyography: EMG of muscles involved in swallowing

can provide information on the timing and relative amplitude

of selected muscles contraction during swallowing. The

electromyogram is recommended to ascertain the presence

of specific nerve or neuromuscular unit deficit such as that

accompanying vocal fold paralysis or to elucidate or corroborate

the presence of systemic myopathy or degenerative disorders.

The goals of a laryngeal EMG are to detect normal from

abnormal activity and localize and assess the severity of a

focal leision by determining whether there is neuroaphraxia

(physiological nerve block or focal injury with intact nerve fibers

or axonotmesis) damage to nerve fibers leading to complete

peripheral degeneration. Laryngeal EMG can evaluate prognosis

too.

The thyroarytenoid muscle is approached by insertion of

a monopolar or concentric electrode through the cricothyroid

ligament midline 0.5cm to 1.0cm then angled superiorly 45 °C and

laterally 20 °C for a total depth of 2cm. The cricothyroid muscle

is reached by inserting the electrode 0.5cm off the midline, then

angling superiorly and laterally 20 degrees towards the inferior

border of thyroid cartilage. Laryngeal EMG help differentiating

neurological vocal cord paralysis from laryngeal joint injury. It

may also confirm the diagnosis of joint dislocation. The 3 areas

of interest for electro diagnostic evaluation of swallowing are the

laryngeal sphincter, the sensory ability of the supraglottic larynx

and pharynx (indirectly evaluated through cricothyroid muscle

function) and the cricopharyngeal sphincter. EMG has several

pitfalls like precise site of lesion cannot be determined except

whether it involves vagus nerve (SLN and RLN). PCA is difficult

to localize through this. Systemic neuromuscular diseases cannot

be differentiated from focal lesions.

Direct laryngoscopy: Endoscopy of the upper aerodigestive

tract is recommended to rule out biopsy or neoplasm that may

be suspected to be the cause of dysphagia or odynophagia.

Occasionally, the endoscopy may be part of the treatment as

in those patients requiring injection of the paralyzed vocal

fold, injection of BOTOX or dilation of the oesophagus for the

treatment of cricopharyngeal achalasia or strictures.

Electroglottography: EGG is designed to track vocal fold

movement by recording the impedance changes as the vocal

folds move toward away from each other during phonation. This

equipment can be modified to track laryngeal elevation which

can be useful in determining the onset and termination of a

pharyngeal swallow and in providing biofeedback to an extent

and duration of laryngeal elevation during the swallows in which

the patient is attempting to improve these swallow parameters.

Esophagoscopy/Gastroscopy: Dysphagia and odynophagia

are common indications for upper Gastro intestinal endoscopy

and may be performed as the initial test in the evaluation of these

disorders. The esophagus is intubated under direct visualization

of hypopharynx. The endoscope is usually advanced through the

upper esophageal sphincter which appears as a slit like opening

in the cricopharyngeous muscle at about 20 cm from the incisor

teeth. The entire length of the esophagus is indirect view of the

endoscope until its termination at the gastroesophageal junction

which lies at the diaphragmatic hiatus.

The esophagus is usually closed at gastroesophageal junction

but this is easily distended with air insufflations. This allows

the endoscope to easily advance through the lower esophageal

sphincter into the stomach. Upper GI flexible endoscopy is the

most specific test for identifying esophageal complications of

GERD, esophageal ulcer, infectious disorders and neoplasms. It

is useful in defining the cause of disease in those patients with

solid food dysphagia.

Cervical Auscultation (Listening to and recording the

sounds of swallowing): Recording the sounds produced during

the swallow by placing a small microphone or accelerometer

on the surface of the patients neck at various locations has

identified some repeatable sounds produced across normal

subjects (Hamlet, Nelson & Patterson, 1990; Patterson, Hamlet,

Fleming & Zones, 1992). Another method for listening to the

sounds of swallowing is to apply a stethoscope to the patients

neck. The ability to distinguish normal from abnormal sounds or

a define the meaning of the sounds produced during swallow by

patients with swallowing disorders has not been determined. It

needs further research.

Cervical auscultation (Sounds of respiration): This can

define inhalatory and expiratory phases of the respiratory cycle

as well as the moment when the pharyngeal swallow occurs

and in which part of the respiratory cycle, swallowing occurs.

If the secretions are in the airway before or after the swallow,

these will also be heard, as will any changes in secretion levels before and after the swallow. Information on secretion levels

and changes in these levels before and after the swallow may be

indicators of aspiration.

Esophageal Ph monitoring: Prolonged (24hour) esophageal

pH monitoring is the most reliable test for diagnosing GERD.

Twenty four hour pH monitoring is usually done following an

overnight fast. The pH catheter is inserted trans-nasally into

the esophagus. Standard placement of the distal probe is at a

position that is approximately 5cm above the proximal border

of the lower esophageal sphincter. It is ultimately attached to

recording device. Patients are asked to record in a diary or in

the recording device, the times that they eat, sleep or perform

any other activities. More importantly, patients will be asked to

record any type of discomfort that they have including all the

symptoms they experience. This information will be used to

correlate the pH at the time a symptom or activity took place and

a symptom index can be calculated. pH should be less than 4 in

normal individuals.

Manometry

- Esophageal manometry.

- Pharyngeal manometry.

Pharyngeal manometry: The response of the oropharynx

to swallowing has two components. The first is compression of

the catheter against the pharyngeal wall by the tongue which

results in a high sharp peaked amplitude pressure wave. This is

followed by low amplitude, long duration wave, which reflects

the initiation of pharyngeal peristalsis. A rapid, high amplitude

pressure upstroke ending in a single sharp peak, followed by a

rapid return to baseline is produced by contraction of middle

and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles to provide mid

pharyngeal response to swallowing.

The pharynx is not radially symmetrical and therefore, the

measurements obtained during standard manometry vary with

the catheter placement. Nonetheless, measurements of intrabolus

pressures during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing may

predict which patients will respond to a surgical myotomy. A

polyvinyl catheter, a thin tube about 35 cm long made of a flexible

polyvinyl material and constructed with multiple pressure

sensors, is passed trans-nasally and the patient is instructed

to perform a series of wet and dry swallows. Lower esophageal

sphincter pressure is measured at baseline and in response to

a swallow. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure is measured

as a step up in pressure from gastric baseline referenced as

atmospheric.

Complete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation with

swallow is demonstrated by a decrease in pressure to gastric

baseline for approximately 6 seconds. Basal, upper esophageal

sphincter pressures can be identified as a rise in pressure above

the esophageal baseline. Due to the asymmetry of the upper

esophageal sphincter, this is normally 50 – 100mm Hg depending

on duration of the pressure sensor (whether lateral or anterior/

posterior). Evaluation of upper esophageal sphincter relaxation

and correlation of sphincter relaxation with pharyngeal

contraction is obtained by instructing the patient to perform a

series of wet swallows.

Acoustical analysis: This is more accessible for speech

language pathologist- done or useful in individuals with mild

dyphagia. Here we will be measuring the swallow sound and

comparing it with the normative developed

Mechanism of the production of glottal sound: It is known

that arytenoids closure, true vocal folds and laryngeal elevation

provide the basis for laryngeal closure during swallowing. The

mechanism of arytenoids closure and true vocal cord closure

valves the larynx shut. In valving the airway during the period

of deglutition apnea, the sub-glottal sound is pressurized. When

the cords apart, there is a release of air and there is a rapid

increase in airflow and the release of this is often audible. Shaker

et al 1990 show that the simple closure at the level of larynx

may not be sufficient to cause the glottal release sound. They say

sudden removal of the valve coupled with elastic recoil of the

lungs provides us with the environment required to produce the

glottal release sound.

Recording of the glottal release sound: Subjects should

be seated in a back straight chair. The cervical region should be

cleansed with a alcohol swipe. The microphone should secured to

the cervical region at the midline of the cricoid cartilage using a

single sided surgical tape such that there is no air escape around

the microphone. Then it should be attached to the preamplifier

which will feed the acoustical signal directly to the computerized speech science lab (CSL 4300, Kay Elemetrics) or any software

which has spectrographic analysis.

Subject should be given trials of water swallow to allow the

investigator to set the optimal recording level. Subjects should

be requested to swallow in one complete action. Recording of the

swallow sound commenced upon the lip cup contact. Recording

ceased post swallow after the laryngeal movement has been

visualized and the individual brought the cup back to the rest

position. Recording should be done directly on to the disk. Each

swallow should be displayed as a raw acoustic signal and linked

by curser and its narrow band spectrogram. The beginning of

swallow sound was marked by combination of auditory feedback

and visual inspection of the spectrogram. Parameters which

need to be measured include frequency, intensity and duration.

This needs to be compared with norms of particular age with

varying thicknesses of fluid as shown in the Table 1 & Figure 1.

Nutritional concerns and assessment in dysphagia

Successful management of dietary needs in dysphagic

patients requires the efforts of all involved caregivers. The

particular responsibility of the dietitian is to assess a patient’s

nutrition and hydration needs and to translate these needs into a

diet that meets restrictions imposed by the team, i.e., oral feeding,

oral feeding with compensatory safeguards or facilitators, enteral

feeding, or combined enternal and oral feeding. As these needs

change, the dietitian should be involved to make the transition

as effective as possible. Another important responsibility of

the dietitian is to make the diet prescribed as appealing and

palatable to a patient as possible.

Both screening and comprehensive nutritional evaluations

require consideration of a patient’s anthropometric

characteristics, dietary intake, relevant clinical and physical

findings and socioeconomic considerations. Comprehensive

assessment will elaborate each of these areas, for example,

dietary intake will be assessed in terms of calories, protein,vitamins, minerals and fluid and evaluated for adequacy based

on the patient’s individual needs.

Indications Nutritional assessment should be considered

when a patient’s mean of feeding has been altered, when such

a change is anticipated, or when there are concerns about the

amount and / or nutrition/hydration value of a patient’s diet.

Populations considered here are those most likely to benefit

from a team evaluation, for example, patients for whom there

are a possibility of safe oral feeding and whose mentation level

is judged adequate for at least a minimal level of cooperation

with team objective. Age groupings of patients have additional

significance. For example, one can expect the CVA (cerebral

vascular accident) population to be older, in general, and the head

trauma population to be younger. Such differences not only have

implications for dietary needs, but also may influence a patient’s

eligibility for funding sources, which support nutritional needs.

In some populations, a change in eating status is anticipated,

and dietary needs can be addressed prior to the expected event.

In other populations, the need for nutritional assistance is acute

and unanticipated. Patients who are apparently well and then

experience a sudden insult, i.e., CVA or trauma are examples of this

kind of population. Other patients may be maintaining adequate

nutrition / hydration but have few reserves to cope with new

or unexpected problems that compromise their nutritional well

being. In such cases, changes in nutrition / hydration status are

not entirely unanticipated. Careful monitoring to assure prompt

intervention is necessary.

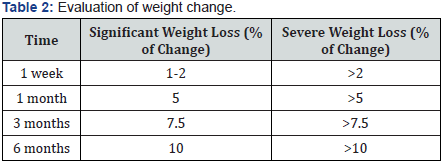

Red flags’ for formal dietitian consult: Significant changes

in weight trends and hydration status in a patient signal the

need for a comprehensive nutritional evaluation. Guidelines

for determining the severity of unintentional weight loss are

presented in Table 2. In general, a person losing 10-20% of his

or her usual weight may sustain moderate impairment, whereas

a loss of greater than 20% of usual weight indicates severe

impairment. In both situations, thorough elaboration of the

cause of weight loss will be required.

Red flags for sub optimal hydration include rapid weight loss

(a 48 hour weight loss of 4 pounds can mean a negative fluid

balance of 2 liters), complaint of thirst, skin turgor changes,

decreased urination, a rising blood-urea-nitrogen level (BUN)

in the absence of other renal indicators, and an increased

serum sodium level (hypernatremia). Patients with thin liquid

dysphagia may be at particular risk for alterations in hydration

status. They will have difficulty augmenting fluid intake to compensate or increased fluid losses due to secondary illness

and are also more vulnerable to other fluid-depleting conditions

(i.e., fever, diarrhea, or increased perspiration related to physical

exertion or heat).

Nutritional assessment: As noted, careful monitoring of

patient’s nutritional status can and should be undertaken by

members of dysphagia team and other caregivers. However,

expedient referral to the dietitian is indicated when there is any

question regarding the patient’s ability to maintain adequate

nutrition / hydration, safely, via the current mean of food intake.

Components of the dietitian’s examination include the following.

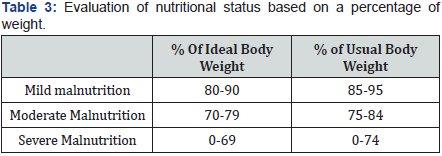

Anthropometric data: As indicated, a primary cue for

dietary referral is weight change. Appropriate weight range is

impacted by gender, age, height and frame. The patient’s usual

weight any change in this amount, over what period of time,

and whether any change was intentional must be determined.

If weight loss is too rapid, and in particular if it is associated

with inadequate protein intake, it may adversely impact the

body’s immune function. The ability to resist disease and

infection is compromised. The patient’s energy level and ability

to participate in the prescribed rehabilitation program may also

be affected. Presented in Table 3 are guidelines for interpreting

nutritional status based on percent of ideal body weight (IBW)

and percent of usual body weight (UBW).

A value of less than 3.5 to 3.2 is suggestive of the patient being

nutritional risk. Other laboratory tests provide a more sensitive

indicator of current protein status but these may require special

ordering procedures. Laboratory values that are both commonly

available and useful for evaluating hydration status are serum

sodium and blood urea nitrogen. Elevated values are typical in

the dehydrated patient. Additionally, albumin will be elevated in

dehydration. One needs to remain mindful that hypo albuminia

may be masked by mild to moderate dehydration, resulting

in a falsely normal appearing albumin value due to hemo

concentration. In dehydration, low urine output will occur as the

body seeks to conserve fluid.

Nutrition history: The patient or caregiver is instructed

to record the time food or drink is consumed, the amount

consumed, and a description of the food and how it was prepared,

i.e., steamed, fried, broiled. The amount of food should be

described using standardized measurements. The patient is also

asked to note if this is a typical meal pattern and, if not, what is

different. Any nutrient label information concerning calories and

protein per serving size should also be included in the report. It

is important to appreciate that merely recording one’s dietary

intake may alter the usual pattern of intake.

Additional measures obtained by the dietitian are a recent

(last 24 hours) food intake record is recalled by the patient

(referred to as a ’24-hour recall’) and a food frequency list, which

describes how often the patient has had different types of foods

over a recent time period. From all measures considered, the

dietitian will compare the patient’s dietary intake to standard

referents of dietary requirements. For example, the USDA

Food Guide Pyramid recommendations for daily dietary

requirements include:

- 6-11 servings from the Bread, Cereal, Rice and Pasta Group (provides the dietary base)

- 2-4 servings from the Fruit Group

- 3-5 servings from the Vegetable Group

- 2-3 servings from the Milk, Yogurt and Cheese Group

- 2-3 servings from the Meat, Poultry, Fish, Dry Beans, Eggs, and Nuts Group.

Subsequent monitoring of weight, laboratory values, and the

patient’s global sense of well being will assist in fine tuning the

nutrition goals.

Clinical and physical findings: It is important to stress

that oral cavity structures and their functional integrity impact

both how and what type of nutrition a patient may be able to

manage. For example, the ability to chew to a ground or puree

texture will determine the texture(s) of food that can be offered

to the patient. Also important to the nutritional evaluation is the

patient’s level of physical activity. If activity is very sedentary,

the patient’s energy need and number of calories required will

be low, necessitating the selection of nutrient dense food. This is

to ensure nutritional adequacy of protein, vitamins and minerals

without excess weight gain that would further impact mobility.

Concurrent chronic conditions, such as diabetes, coronary

artery disease, renal and pulmonary impairment that may have

pre-existing diet management in place, must also be noted. A

cardiac patient’s low diet may be inappropriate if the patient is

unable to consume adequate calories while adhering to the low

fat regimen. The initial priority is to maintain weight. Once this

is achieved, a patient may begin incorporating lower fat food

choices if the low fat diet is still desirable. Diabetic diets have

undergone significant changes since 1994. The emphasis is on

individualizing the diet based on the medical nutrition needs.

Alterations in cognitive skills, ability to attend, or to speak

will of course affect communication and social interaction and

have implications for a patient’s compliance with treatment

objectives. Such changes may also trigger depression or a

diminished sense of well being, with resultant decreased appetite

and failure to maintain weight.

Pediatric feeding assessment: Pediatric feeding problems

have been recognized in the literature for the past 30 years.

Although no comprehensive definition of pediatric feeding

problems has been widely accepted, infants and children experiencing feeding difficulties demonstrate either a refusal to

eat orally and / or are unable to sustain oral feedings to maintain

adequate caloric intake. Numerous articles have identified

groups of children who are at risk for feeding problems. See table

for etiologies commonly associated with feeding problems.

Common etiologies associated with feeding problems- Neurological dysfunction.

- Gastrointestinal disease/dysfunction.

- Cardio-respiratory compromise.

- Sensory deprivation.

- Structural anomalies.

- Social-behavioral maladaptation.

A feeding assessment is a comprehensive, systematic

biopsychosocial approach to the evaluation of a child who has

feeding difficulties. The assessment can help professionals

identify potential or actual feeding problems and develop

appropriate interventions.

Pediatric Feeding Assessment- The feeding assessment consists of five parts:

- Case history (obtained prior to evaluating child)

- Nutritional screening, Feeding history, Developmental milestones (obtained from parent or caregiver’s interview)

- Physical Assessment

- Oral reflexes and feeding skills assessment

- Psychosocial international assessment.

Case History

Done before the evaluation of the child. It includes a review

of the infant or child’s:

- Medical history.

- Growth chart.

- Current clinical nutritional status.

Medical history

The medical history review includes evaluating the

perinatal and neonatal history, medical diagnosis, previous

hospitalizations, and significant illnesses. The perinatal and

neonatal history may provide information detailing any fetal

distress, the infant’s response during delivery, prematurity, any

significant congenital anomalies, and any major illness during

the first month of life. Congenital anomalies, central nervous

system insults, or chronic illnesses may affect the child’s ability

to eat orally. Previous hospitalizations and significant illness

can influence the child’s developmental skills including feeding

skills. Child’s refusal to eat, oral motor organization, and / or

ability to sustain adequate oral intake.

Growth chart: It is critical to

review to growth chart to

determine the child’s nutritional status. Prolonged inadequate caloric

intake results in an infant or child nutritionally failing to

thrive. A child is defined as having failure to thrive when:

- The weight for length ratio is <5%

- The weight is <5% or

- The weight percentage has decreased two standard deviations or more.

Other growth charts for some specific patient populations,

such as Down’s syndrome and premature infants, are available.

Current clinical nutritional status: A review of the current

clinical nutritional status should include laboratory tests and

anthropometrics. Laboratory tests can help define nutritional

deficiencies. The most readily available screening tests are

the complete blood count and a chemistry panel. Protein

deficiency (i.e., a low albumin and total protein). Anthropometric

assessment measures triceps, skin fold thickness and mid arm

circumference as a serial indicator of body fat and muscle mass.

Anthropometrics may be a preferred measurement of nutritional

status compared to growth charts when the infant or child’s age

is unclear.

Nutritional screening, feeding history and development

milestones: This information should be elicited from the parent

or caregivers. The feeding history needs to include the parent’s

perception of the feeding problem or difficulty and a thorough

description of the child’s mealtimes. The history should include

type of food, amounts, textures, duration of feeding, physical

environment, and family members usually present, the child’s

behavior, and any interventions tried. A 24-hour dietary recall

of the child’s feeding routine is helpful to assess individual

nutritional patterns.

Physical assessment

An assessment of the child’s general physical appearance and

findings will provide information about the child’s nutritional

status. When performing this assessment, one must consider the

infant or children;

- Behavior.

- Development.

- Physical appearance.

Behavior: When observing the behavioral state, observe

how the child acts. Is the child alert, active, irritable or apathetic?

The alert and rested child provides the most realistic information

about feeding behaviors. Irritability and apathy are commonly

seen with malnutrition.

Development: The developmental assessment involves

observing the child’s fine and gross motor skills and muscle tone.

Is the child performing tasks at the expected age, or is the child

showing some developmental delays? Most children who are

developmentally delayed exhibit some alteration in muscle tone,

either hypertonia or hypotonia. Both the child’s motor skills and

muscle tone influence his or her ability to eat.

Physical appearance: The physical appearance involves

assessing the child’s:

- Skin.

- Hair.

- Eyes.

- Mouth and oral cavity.

Skin: First, check the skin for color, bruises, rashes, and

turgor. A pale color may indicate iron-deficiency anemia.

Bruising may be due to vitamin K deficiency. Essential fatty

acids, zinc or vitamin deficiencies are known to cause skin

rashes. When inadequate fluid intake accompanies poor caloric

intake, the skin will be dry. Loose skin covering the decreased

subcutaneous fat indicates both a calorie and protein inadequacy

(marasmus). Excessive fluid retention resulting in edema may be

due to insufficient protein intake (kwashiorkor) or electrolyte

imbalances.

Hair: Check hair for texture, color and distribution. Hair that

is brittle, pale blond colored and sparsely distributed is seen

with protein malnutrition.

Eyes: Check eyes for hydration status and infection.

Xerophthalmia, or dryness, may be due to vitamin A deficiency.

Malnutrition can affect the immune system and cause

conjunctivitis.

Mouthand oral cavity: The physical appearance of the

mouth and oral cavity portion are checked as part of the oral

reflexes and feeding skills evaluation.

Psychosocial feeding assessment: The relationship

and interaction between parents and infant or caregiver are

important. This interaction may have profound effects on the

child’s nutrition and feeding. For ex, the parents may be confused

and not offer food to their infant if the infant does not provide

clear hunger cues (ie, agitation, crying and mouth opening).

In cobtrast, the infant who does provide clear cues may not be

offered food coz parents are insensitive to those cues. Therefore

the quality of interaction between parents and their infants have

a very significant impact on the amount of food ingested even if

the infant has normal feeding skills. An interaction assessment

tool such as Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCFAS).This provides information about the relationship between the

child and parents.

Oral reflexes and feeding skills: The infant or child’s

reflexes and feeding skills determine the types of foods safely

handled. During the first 3 years of life, dramatic oral motor

and developmental feeding skill changes have profound effects

on the types of food, textures, and feeding methods and the

infant/child can safely control. The approach recommended for

assessing oral reflexes and feeding skills is to progress from the

least frightening or threatening (external touching of the face

and mouth) to the most threatening (internal inspection of the

mouth).

Some oral reflexes are common to all ages, but the most rapid

oral reflex are feeding skills changes occur in infancy. Therefore,

the oral reflexes and feeding skills assessments will be divided

into eight infant developmental stages covering the 3 years of

life.

To know more about Journal of Head Neck please

click on :

To know more about Open access Journals

Publishers please click on : Juniper Publishers

Comments

Post a Comment