Latex Allergy: Overview and Recommendations for the Perioperative Management of High-Risk Patients-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Open Access Journal of Head Neck & Spine Surgery

Latex Allergy: Overview and Recommendations for the Perioperative Management of High-Risk Patients

Abstract

Latex allergy affects about 1% of the general population and is the second leading cause of perioperative anaphylaxis after muscle relaxants. Hypersensitivity reactions associated with latex range from localized to potentially fatal anaphylactic reactions. Since it has been shown that more frequent cause for development of these reactions is exposure to latex, several measures have been implemented to reduce the prevalence of latex allergy and thus potentially dangerous reactions associated, especially in the high-risk population as patients with congenital malformations of the central nervous system. Despite existing efforts, there is still a lot of misinformation on this issue. The objectives of this review are to report on this condition, inform about the main strategies to prevent sensitization, provide guidelines for surgical management of sensitized patients and give information that allows the clinician identify and study a possible allergic reaction to latex during the perioperative.

Keywords: Hypersensitivity; Anaphylaxis; Latex; Rubber

Introduction

Latex is a natural substance that comes from the sap of the rubber tree. It is a material widely used in the manufacture of domestic, industrial and especially medical products [1]. The prevalence of latex allergy in the general population is estimated between 0.8 and 6.5% [2], and the repeated exposure to this material is the most significant risk factor for its development [3]. Among the main risk groups are health personnel, where the incidence reaches 17%, and patients with spina bifida where 73% incidence has been described [4] (Table 1). Factors as age, race or sex are not associated with an increase in risk.

Worldwide, it is estimated that in one of every 3.500 to 20.000 surgeries an anaphylactic reaction occurs, which represents about 9% to 19% of all surgical complications, with a mortality varying between 3% and 9% [5]. About 50% of the medical devices contain latex [6], so it is not a surprise that this material is the second cause of perioperative anaphylaxis, being responsible in the 12 to 16.7% of cases [7]. Fortunately, this incidence has decreased significantly since hospitals and outpatient surgery facilities have adopted latex-free policies [5]. Based on this background, latex allergy is a condition of special interest to the healthcare professionals. This review of the literature seeks to expose the relevant basic concepts about allergic reactions to latex, as well as to generate guidelines for the perioperative management of sensitized patients.

Sensitization mechanisms and immunological associated to latex reactions

Latex allergy is associated to any immunologically mediated reaction to this material, associated with clinical symptoms. Since the 1980s, there has been an increase in the incidence of allergic reactions to latex, associated with the introduction of mandatory use of gloves within universal precautions in the prevention of infectious diseases such as HIV, Hepatitis B and C [1,3,8]. Sensitization depends on factors such as the route, dose, frequency of exposure, and individual susceptibility [2,4,9]. Exposure may occur as a result of direct contact with skin or mucous membranes, a wound inoculation, or ingestion.

Another type of exposure occurs when the latex proteins bind to the dust that contain these products, volatilizing during the placement and removal of gloves, being inhaled and to enter the respiratory tract [10].

It has been shown that these particles can remain suspended in the environment for up to 5hours [4,11]. The amount of exposure needed to sensitize a person is unclear, and the threshold required to trigger an allergical response varies considerably among individuals [12,13]. Is possible to describe three types of allergic reactions to latex:

Irritant contact dermatitis: It is the most common type of allergic reaction. Can develop within minutes or hours after exposure, due to mechanical or chemical skin irritation by the components used in the product manufacturing process [3]. Clinically it is characterized to present as pruritus, rash, scaling, burning sensation, inflammation or blistering [8]. No previous sensitization is necessary for the development of dermatitis, but this condition facilitates the progress of an immunologically mediated hypersensitivity reaction, because the lost of skin integrity favors the direct exposure to allergens [14].

Allergic contact dermatitis or type IV hypersensitivity reaction: Reaction mediated by cellular immunity. It occurs between 6 and 48hours after contact with latex, but is usually produced by other allergens from the chemicals used in the production process [8]. T lymphocytes are sensitized and infiltrate the contact zone on the skin [1]. The symptoms are similar to those of irritative contact dermatitis (erythema, vesicles and desquamation) and do not require a history of previous contact to manifest itself [7].

Type I hypersensitivity reaction: It occurs after minutes of exposure, either by the cutaneous, mucosal or aerial route. It requires prior sensitization with latex proteins and production of IgE antibodies. Clinically, it can present as a localized urticaria to a frank anaphylactic reaction. Moderate reactions include rhinitis and conjunctivitis, and are more likely to occur due air exposure or skin contact.

Eighty percent of the reactions associated to latex correspond to contact dermatitis or type IV hypersensitive and occur mainly in response to chemicals used in the manufacture of these products [12]. Only type I hypersensitivity corresponds to a response to proteins in the latex [8]. This reaction is less frequent but can generate large complications and life threatening if it is developed during the perioperative period.

Identification of allergic patients or at potential risk

High-risk populations are those that are frequently exposed to latex elements, such as patients undergoing multiple surgical procedures, health personnel, rubber workers, and individuals with a history of atopy [1]. These populations are at increased risk of developing more frequent and severe allergic reactions [5]. In particular, patients with congenital malformations of the central nervous system give especial interest. In patients with spina bifida, incidence of latex allergy has been reported in 35% to 73% [4,15]. These patients have also show increased sensitization to latex protein and a significant increase in levels of fully and specific latex IgE from the perinatal period, which could be associated with the occurrence of allergy in the future [16]. Another example is patients diagnosed with myelomeningocele, with an estimated incidence of 19.51% latex allergy, and 18% of sensitized patients [17]. The most important risk factor to the development of allergy in these cases is the history of 5 or more surgical interventions [17,18].

Deep clinical history minimizes the risk of new exposure in sensitized individuals during prior medical and dental procedures. The anamnesis should emphasize on risk factors, such as exposure to latex, spina bifida, reconstructive urologic surgery, multiple surgical procedures, intolerance to latex products [balloons, gloves, preservatives, dental rubber dams), allergy to fruits, history of intraoperative anaphylaxis of unknown cause, or health personnel with a history of atopy [4] (Table 2). It is estimated that in 30% of cases of anaphylaxis, there is a suggestive history of previous reactions [7]. Individuals with allergies to some specific foods are at increased risk of develop allergic reactions to latex. Although the mechanism is not clear, some proteins present in certain fruits may act similarly to the latex allergenic proteins and produce sensitization [1]. It has been reported that between 21.2% and 86% of patients with documented allergy to latex also had a food allergy. Some of the foods that could produce cross-reaction with latex include banana, avocado, kiwi, grapefruit, papayas, almonds, chestnut, pineapple and tomatoes among others [6]. Allergy to these foods may precede allergy to latex or vice versa.

Prevention Strategies

The best treatment is to avoid exposure [1,12]. The incidence of anaphylactic reactions to latex has decreased due to the identification of high-risk patients, better diagnostic tests and preventive measures [3]. For patients with spina bifida treated in latex-free environments, incidence of latex allergy seems to be similar to the general population. More specifically, it has been reported an incidence of 5% sensitization and 0.8% of allergies in patients with spina bifida hospitalized in latex-free environments, versus 55% and 37%, respectively, in patients managed in environments without restriction to exposure to latex [19].

Given that in most cases is not feasible to have 100% latex-free environments, is essential to at least generate a safe environment for patients with prior allergy history to this material. This is usually sufficient and is more achievable than an environment completely free of latex [11]. These general measures include adequate identification of allergic patients, proper labeling of products formulated with latex and use of latex-free gloves. Among the general recommendations for health establishments is important to educate staff, establish clear protocols for the management of these patients, have a latex-free cart available and check the latex contents of the entire surgical team.

The antigen content in latex products can vary significantly. Products manufactured with an “immersion” process (eg gloves and preservatives) have the highest levels of allergens, whereas dry rubber (eg tires, rubber seals, plugs and plugs of vials and syringes) are less allergenic [8]. It is important to note that products labeled as hypoallergenic have fewer chemicals responsible for causing allergic reactions, skin irritation and dermatitis, but this labeling is not related to the latex content of these products [11,14]. The two main prevention strategies are:

Use of latex free gloves: There is important evidence that latex gloves are the main source of allergens in health care settings [12]. These have been the most popular given their characteristics, which include strength, elasticity and superior protection qualities. It has been shown that the level of aeroallergens in the environment is strongly correlated with the use of gloves with high content of allergens and dust, total number of gloves used and hours of activity in the environment. Studies have shown that changing gloves with high dust content by gloves with low amounts or dust-free (which are low in proteins and allergens) results in a significant reduction of aeroallergens and a dramatic decrease in the incidence of latex allergy. It has also been reported that after removing latex gloves at work sites, the levels of aeroallergens are reduced to undetectable levels after 24hrs [8].

Concern about latex allergy has led to alternatives such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) gloves or nitrile gloves. It seems to be that PVC gloves filter more than latex gloves (63% filtration in PVC gloves, versus 7% latex gloves), but on the other hand nitrile gloves have shown a better performance than those of PVC. Unfortunately routine use has received some resistance [12] and latex gloves continue to be a cheap alternative, offering appropriate protection and other essential qualities for safe and effective performance.

Pre-medication: The role of pre-medication with H1 antagonists and corticosteroids is not well defined. These medications may help to decrease non-IgE-mediated reactions. However, they do not prevent IgE-mediated immune reactions [7,12,20]. Avoiding exposure to the allergen is the only way to avoid an anaphylactic reaction.

Surgical Management Protocol for Patients with Latex Allergy [2,4,13]

The following measures are aimed at promoting safe care during the perioperative period in patients at risk for an allergic reaction to latex, either by medical history or because they have positive laboratory tests:

Preparation of the surgical theater and preoperative period [2,13]

- The procedure or surgery should be scheduled first thing in the morning, when the levels of aeroallergens are lower.

- Install a label on the door of the operating room that identifies the patient as allergic and to the room as latex-free.

- The day before surgery, remove all products containing latex (reserve bags, endotracheal tubes and laryngeal masks that are not latex-free).

- Cleaning staff of the surgical room should not wear latex gloves. The day of the surgery, the surfaces should be cleaned again to remove the suspended powder.

- When appropriate, the mattress should be protected with double bed sheet.

- Cover all monitoring devices, cables/tubes (oximeter, blood pressure, electrocardiogram) to avoid direct contact with the skin.

- Products sterilized in ethylene oxide must be rinsed before use. Residual ethylene oxide reacts and may cause an allergic response in a patient allergic to latex.

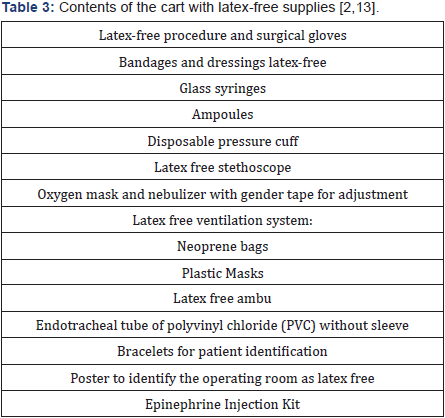

- A cart with latex-free supplies (Table 3) should be available inside the operating room.

- The operating room should be adequately equipped to handle an unexpected anaphylactic reaction and have immediate availability of epinephrine.

- Allergic patients should be identified at the time of admission with: a bracelet, in the medical history and in the sheets of nursing.

- Before the pressure is taken, the arm should be covered with a cotton mesh and auscultated through it, avoiding that the stethoscope has contact with the skin.

- The patient should wear a cap without elastic and gender boots.

Intraoperative period

- All the surgical team should wear latex free gloves.

- The traffic inside the surgery room should be minimal.

- Do not use penrose drains, latex bands, latex irrigation elements (eg irrigation pears).

- Latex-free or glass syringes should be used.

- Medications should be preferred in glass ampoules. If not available, remove the rubber stoppers before preparing the medication.

- Medications should be prepared immediately prior their administration to minimize contact with the syringe plunger.

Postoperative period

- The postoperative period should be performed in the room prepared for the patient or inside the same operating room.

- All departments involved must be informed of the presence of patients allergic to latex, so that they can take the necessary precautions to protect them.

Detection and management of an allergic latex reaction

Since the allergen is generally absorbed slowly from the surgeon’s glove, the reaction usually occurs about 30 minutes after contact with the skin and mucous membranes during the maintenance of anesthesia, not during the induction period. However, the actual start of the reaction may range from 10 to 290minutes [13]. This interval will depend on the sensitivity of the patient, amount of allergen absorbed and the contact surface (absorption is faster through the peritoneum or vaginal mucosa than through the skin) [7]. Except for these characteristics, latex reactions are similar in their manifestation to those reactions caused by other agents during surgical and medical procedures [2] such as muscle relaxants or antimicrobials.

The management of an intraoperative anaphylactic reaction is well-documented [4,5,13,21] and includes pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures according to the clinical presentation, course of the condition and the context in which anaphylaxis occurs. In the particular case that the reaction is suspected to be caused by an undiagnosed allergy to latex, the following measures should be incorporated as part of the management:

- Stop or minimize the absorption of the agent (consider the variety of possible routes of exposure).

- Remove all products containing latex and change to latex-free gloves.

- Place an allergy alert to the latex in a visible place at the entrance and inside the surgery room.

- Complete the study of the patient after the reaction.

In mild cases, spontaneous recovery may be observed even in the absence of any specific treatment. In such circumstances, lack of proper diagnosis and evaluation can lead to fatal re-exposure [20]. Any suspected hypersensitivity reaction during anesthesia should be extensively investigated through a detailed history of the reaction, with emphasis on concomitant pathologies, known allergies, previous anesthetic history and the stage of anesthesia were the reaction occurred, in addition to performing laboratory tests according to each case [7]. Immediate tests have been designed primarily to determine whether or not an allergic mechanism is involved in the reaction, while late testing seeks to identify the drug responsible and possible alternatives to its use [20]. Among the tests available for the study of latex allergy are:

Serum tryptase: Indication of mast cell activation. It rises in mediated and non-IgE mediated reactions. A concentration above 25mcg/ml might suggest a type I reaction [5,7]. The recommendation is to take serial samples immediately, at 2, 6 and 24 hours, after the reaction. It has a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 89% for anaphylaxis. The absence of a high tryptase does not exclude an anaphylactic reaction.

Serum-specific IgE: The recommendation to perform this test after 4 to 6 weeks and before 6 months of the event. Immediate measurement could give a false negative. The sensitivity of IgE tests is variable; for latex is about 92%.

Skin tests: They can be done up to one year after the event, but not immediately to avoid a false negative. The recommendation is to wait 4 to 6 weeks after the reaction.

Prick test: Evaluates the sensitization to the latex, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100% [4]. Only IgE-mediated reactions can be studied with cutaneous tests [7], since they do not identify non-immunologically mediated reactions [5].

Patch test: Is recommended for the study of latex contact dermatitis. Additives used in the glove manufacturing process should be included, since delayed hypersensitivity is rarely due to allergens characteristic of unprocessed latex [14].

Conclusion

Although achieving completely latex-free environments is unrealistic, every effort should be made to minimize the risk of sensitization, especially in high-risk groups such as patients with congenital malformations requiring multiple surgical interventions during their early years of life. In addition, it is important to consider that achieving an environment with low levels of allergens is an issue that not only involves the safety of the allergic patient. The implementation of these measures has a significant impact on the sensitization of exposed health personnel and barriers to protection against infectious diseases.

The management of latex allergy should be approached from different perspectives and multidisciplinary support should be obtained to:

- Establish policies for the identification and care of patients with known allergy to latex;

- Develop policies and procedures for health workers with latex allergy;

- Provide environmental control and resource management to minimize unnecessary exposure of patients and staff to materials with a high content of latex antigens; and,

- Promote the ongoing training of patients and employees on the topic of latex allergy.

For more articles in Open access Journal of Head Neck & Spine Surgery | please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jhnss/index.php

For more about Juniper Publishers | please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/pdf/Peer-Review-System.pdf

Comments

Post a Comment