Cochlear Endoscopy in Cochlear Implantation of a X-Linked Stapes Gusher Syndrome-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF HEAD NECK & SPINE SURGERY

Abstract

A 12-year-old boy with a five-year history of

bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and X-linked stapes gusher syndrome

developed progressive left-sided hearing loss. The pre-operative

computed tomography of the temporal bone showed a bulbous internal

auditory canal with a dysplastic cochlea and no apparent modiolus. A

1.3mm salivary endoscope was placed at the cochlear entrance to assess

the intracochlear anatomy. This revealed membranous structures of the

cochlea without direct communication to the internal auditory canal. We

advocate for the use of cochlear endoscopy to better delineate inner ear

anatomy, which will influence the implant selection and potentially

hearing outcomes in patients.

Keywords:MCochlear endoscopy; Otoendoscopy; X-linked stapes gusher syndrome; Cochlear implant; Perilymphatic gusher.

X-linked stapes gusher syndrome (otherwise known as

X-linked deafness type 3 or Nance deafness) is a rare form of

sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) syndrome. Inherited in a sex-linked

recessive manner, it is believed to be the consequence of a

loss-of-function mutation on the X-chromosome in the POU3F4 gene at the

DFN3 locus [1,2]. Males tend to present greater phenotypic severity than

females, who present less frequently [3-5].

Affected patients have an abnormal configuration of

the lamina cribrosa and internal auditory canal (IAC) [1,3,4,6,7]. This

malformation leads to increased perilymphatic pressure and to stapes’

footplate fixation, giving rise to conductive hearing loss and

progressive cochlear nerve incompetence. This is relevant for surgeons,

as it results in an increased risk of perilymph gusher with surgical

manipulation [1,3,4,6,7]. This may lead to other complications, such as

otorrhea, rhinorrhea, and recurrent meningitis [8]. Meningitis

complicating cochlear implantation (CI), occurs at a higher rate in

patients with inner ear (IE) abnormalities, including X-linked gusher

syndrome [3,9].

Traditional approaches to imaging for CI utilize

computed tomography of the temporal bone (CT TB) and/or magnetic

resonance imaging. We report a case whereby intra-operative

otoendoscopic visualization allowed for real time visualization of the

IE anatomy, which allowed us to optimize our electrode

choice for CI. In this case, such visualization was valuable, as it

indicated the presence of the membranous portions of the IE to evaluate

if the modiolus was present, which we believe implied that a directional

electrode was the most appropriate choice.

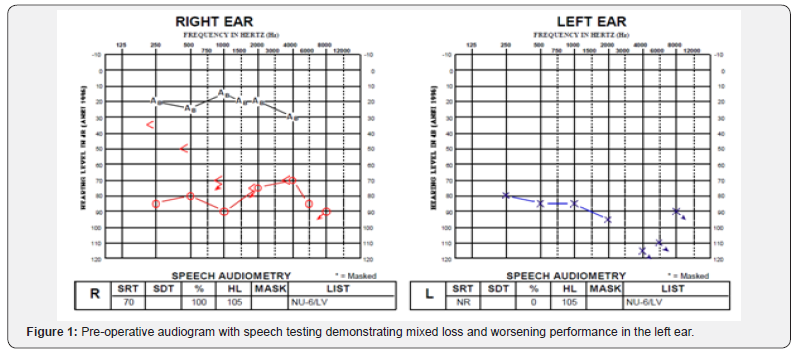

A 12-year-old boy with a five year history of

bilateral SNHL and X-linked stapes gusher syndrome presented with

progressively worsening left-sided hearing loss. He was initially

performing well with bilateral traditional hearing aids but developed

progressive mixed loss and worsening performance in his left ear. His

preoperative audiogram can be seen in Figure 1. He was sent for CI

candidacy assessment and was deemed to be suitable.

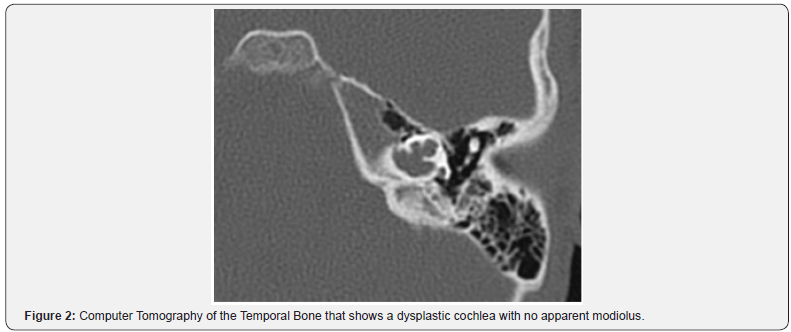

The pre-operative computed tomography (CT) of the

temporal bone was assessed. This showed a bulbous IAC with

a dysplastic cochlea and no apparent modiolus (Figure 2).

A CI24RE (ST) implant was initially selected by the implant

team due to the uncertainty regarding the location of the spiral

ganglion cells.

A 1mm cochleostomy was made anteroinferior to the

round window (RW). Upon entering the cochlea, a moderate

perilymphatic gusher was encountered. A 1.3mm rigid salivary

endoscope (Karl Storz, Germany) with a 3-chip full HD camera

head (Image1 S H3-Z) was approached trans-tympannically and

was placed at the edge of the 1mm cochleostomy to assess the

intracochlear anatomy.

To avoid injury to the inner ear, the CSF was not suctioned.

The same view was not achieved with the microscope as the

endoscope provided a more magnified and higher definition

view of the modiolus. There was evidence of membranous

structures of the cochlea without direct communication to the

IAC. Full insertion was achieved on the first attempt without

any difficulty and the gusher was controlled with packing of

periosteal tissue at the cochleostomy site. An intra-operative

plain X-ray confirmed the electrode placement.

When the cochlear modiolus and osseous spiral lamina

are

deficient, the absence of a bony septum creates a common space

seen on the imaging study [10] (Figure 2); there is an abnormal

communication between the IAC and the vestibule responsible

for the periphymphatic gusher. Patients with IE anomalies may

have both atypical positions of their spiral ganglion cells (SGC)

and have a higher likelihood of having fewer spiral ganglion cells

[11]. This has functional implications because at least 10,000

functional SGNs are necessary for effective speech discrimination 12].

Also this number can be further reduced by surgical trauma

[12]. Therefore, choosing the proper electrode device, namely, a

directional or a full banded electrode can help reduce the number

of lost SGNs. The fully banded CI electrode may be more useful in

the absence of a modiolus to allow for full and multi-directional

stimulation, whereas the pre-curved directional electrode may

be more appropriate if there is a modiolus present for precise

stimulation [13].

The proper electrode choice may have important hearing

outcome implications for patients with IE anomalies following

CI due to the challenges of reaching an optimal level of cochlear

stimulation, decreased dynamic range, a wider pulse width,

and weakened neural synchrony [7]. The functionality of CI is

correlated to the number of SGCs and their distances from the

stimulating electrode [14].

In our patient, we assumed that there was no IAC

communication due to the presence of modiolus. The moderate

CSF gusher was presumed to be secondary to his X-lined stapes

gusher syndrome and his enlarged IAC. Perilymph gusher during

CI in patients with X-linked gusher syndrome is inevitable, but a

thorough examination of the IE is still critical. CT of the temporal

bone is important for surgical planning, and it is also useful to

assess the likelihood of perilymphatic gusher [4]. Distinguishing

features on imaging include an enlarged bulbous IAC, a widened

cochlear aperture without the lamina cribrosa, cochlear

hypoplasia with modiolar deficiency, and a broadening of the

bony canal for the labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve [6].

Enlarged vestibular aqueducts may also appear in conjunction

with modiolar deficiency [15].

The rarity of X-linked gusher syndrome may result in

radiologists failing to recognize these signs, which may mislead

surgeons to perform stapedectomies that are otherwise

contraindicated. Thus, Incesulu et al. [3] advocated for high

resolution CT of the temperal bone to assess for congenital

dysplasia with ¬at least 1-mm thick slices [as opposed to 2mm

thick slices], which should ideally be assessed by an experienced

neuroradiologist [3]. Quan et al. [16] proposed that CT virtual

endoscopy should be done to evaluate CT data through threedimensional

reconstruction [16]. Limitations to both modes

of assessment assume that the CT images correlate perfectly

with the anatomy of the IE and that consistent radiological

consultation will occur. Our case, however, demonstrated that

intra-operative endoscopic findings do not always correlate with

CT findings, indicating that cochlear endoscopy may be a useful

tool to better delineate the intracochlear anatomy.

The otoendoscopic intracochlear view gave us accurate and

real-time information on the anatomy of the IE, which confirmed

the presence of a modiolus and the confidence that the CI would

not be in the IAC. This has the potential to allow us to make a

better-informed decision regarding the type of electrode to place.

Electrode choice is significant for patients with IE

abnormalities, since the location of neural tissue may be

abnormal. In patients that have an absent modiolus, a

circumferentially stimulating electrode may be preferred over

a full-banded electrode, which may risk adverse facial nerve

stimulation [3]. One explanation for post-operative facial nerve

stimulation in children with IE abnormalities is the close vicinity

of the electrode to the nerve [14]. Therefore, to avoid injury, the

proper choice in electrode should be made.

While CT temporal bone has served as the conventional

approach to assessing the anatomy of the IE, fthe endoscope

offers better resolution of the modiolus than the CT temporal

bone, as the CT indicated that there was no modiolus. We

advocate the use of intracochlear endoscopy in selected cases as

it offers a better resolution than even high-resolution CT. With

the potential to change electrode choices in CI, the customization

of electrode choice based on the presence of membranous IE

anatomy may change the hearing outcome of the patients with

anomalous IE anatomy and patients with uncertain location of

spiral ganglion cells.

To know more about Open Access Journal of

Head Neck & Spine Surgery please click on:

To know more about Open access Journals

Publishers please click on : Juniper Publishers

To know more about juniper publishers: https://juniperpublishers.business.site/

Comments

Post a Comment