Ticks in the External Auditory Canal: A Common Situation in Rural Areas-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF HEAD NECK & SPINE SURGERY

Abstract

Objective: Foreign bodies in the external

auditory canal generally occur in children, and are generally inert.

Ticks constitute live foreign bodies. This is important, because ticks

are vectors of many diseases, including Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever.

This article throw as light into a clinical problem seen frequently

especially in rural population.

Material and Method: Patients living in

rural areas diagnosed with ticks in the external auditory canal were

retrospectively studied. Twenty- one patients treated in

otorhinolaryngology clinic in the Northeast Anatolian region of Turkey

were examined in terms of demographic and seasonal features, diagnosis,

treatment, and follow-up.

Results: The usual complaint was increasing ear pain. On parasitological examination, all ticks were Otobius megnini. No patient developed Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever or any other illness.

Conclusion: Of living foreign bodies in the

external auditory canal, ticks are common in our country (especially in

rural areas). Although no Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever have been

noted, preventive measures are required.

Introduction

Foreign bodies in the external auditory canal

(FBEAC) are frequently encountered in otolaryngology outpatient clinics

and emergency departments, generally in children under 6 years of age.

The most common foreign bodies are fruit nuclei, nuts, toys, beads, and

(sometimes) living foreign bodies [1-3].

Ticks are obligatory blood-sucking arthropods and

more than 900 species are known. Approximately 46 species are found in

Turkey [4,5].

Such ectoparasites transmit typhus, Q fever, tularemia, Lyme disease,

and Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF); the latter causes high-level

human mortality [6-8].

Materials and Methods

For ethical consideration, application was made to

local Education and Research Hospital Ethics Committee. The Ethics

Committee approved the admission on 5 January 2016 with decision number

2016/1-2. In addition, informed consent was obtained from all the

patients included in the study.

Between May 2014 and May 2016, 21 patients

diagnosed with ticks in the EAC at the otorhinolaryngology clinic were

retrospectively evaluated. Patient age, gender, occupation, area of

residence, complaints, examination findings, treatment, and follow-up

were recorded.

When ticks in the EAC were first identified,

medical staff donned personal protective equipment (masks, glasses,

gloves, and aprons) and the ticks were removed via autendoscopy using

alligator forceps or curettes. Each tick was placed in a bottle and

labeled. The EAC was washed with ciprofloxacin. Patients were then

evaluated in terms of fever, headache, widespread body pain, arthralgia,

malaise, diarrhea, and bleeding; and a complete blood count was

performed. The patients were then told of the findings and followed-up

for 7 days. This follow-up was done especially to exclude the CCHF. The

ticks were examined parasitologically. The statistical analyses were

performed using SPSS 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Two of the 21 patients were male and 19 female.

All patients (average age of 42.3 years; range 21 to 69 years) were

engaged in animal husbandry (especially milking) in rural areas (Table 1).

Most patients visited in spring and summer. The complaints were ear

fullness, pain, hearing loss, and a sense of motion in the ear. Ten

ticks were in the right ear and 11 in the left ear. One patient had

three ticks in the same ear. All ticks were in the inner one-third of

the EAC (Figure 1).

All of the patients were involved in animal husbandry and most presented in spring and summer.

The ticks were removed under local anesthesia; we

first attempted to catch them as they moved. If this was not possible,

we broke the grip using a curette and then removed the tick.

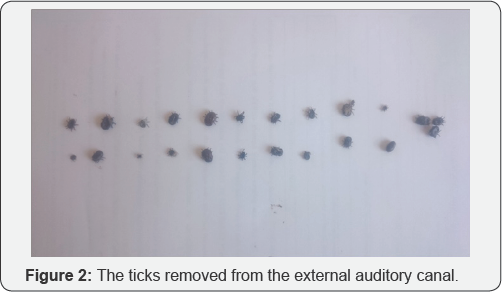

Parasitological examination revealed that all ticks were Otobius Megnini (Figure 2). On full blood counts, all patients were normal and no symptoms were observed to the end of the 7-day follow- up.

Discussion

Ticks are obligatory blood-sucking arthropods

distributed worldwide and transmit many viral, bacterial, and parasitic

infections to humans [8].

Ticks are divided into two main groups, the Ixodidae (which are stiff)

and the Argasidae (which are soft). Approximately 80% of all ticks are

stiff and the rest soft. Soft ticks are divided into four groups: Argas,

Carios, Ornithodoros, and Otobius [5]. The ear tick is Otobius Megnini [9]. All ticks of the present study were of this species, as expected.

Typhus, Q fever, tularemia, lyme disease, and CCHF

are tick- transmitted diseases; CCHF causes high-level human mortality.

Fortunately, no case of CCHF transmitted by a tick in the EAC has yet

been reported. Ticks can produce toxins causing irritation, facial

paralysis, and allergies [10].

Of the various FBEAC, ticks are rare [9,11]. However, in some studies (especially that of Naik et al. [10])

ticks were not infrequent in the EAC; geographical and developmental

features of the regions where studies are conducted are in play [5].

The risk of tick contact increases for those engaged in agriculture and

animal husbandry; in spring and summer; and when picnicking [6]. As in other reports, all of our patients were involved in animal husbandry and most presented in spring and summer Patients with EAC ticks often complain of pain.

Other complaints include fullness, hearing loss, tinnitus, and the sense

of a moving object [9-11]. Pain can be very severe, depending on the size and location of the tick in the EAC [10]. The most common symptom in our present study was increasing pain as the tick grew over time by sucking blood.

General anesthesia may be required during

treatment; FBEAC are often seen in children. Additionally, some reports

have stated that general anesthesia may be required for tick removal [10]. However, as ticks are usually found in adults, removal under local anesthesia is generally possible [3,5,10].

Alligator forceps and ear curettes can be used to this end. If

alligator forceps are employed, they should grip hard rather than soft

tick tissue because, if soft tissue is gripped, the tick’s contents may

drain into the EAC. After tick removal, the EAC should be washed with an

antibiotic solution to prevent secondary infection. The patient should

be told about the risk of infectious diease; and follow- up scheduled.

As mentioned previously, this study consists of patients only living in

the rural area where our hospital is located. And all of the patients

are adults. These seem to be the shortcomings of the study.

Ticks in the EAC are common in rural areas,

especially in those who work in agriculture and with livestock. Although

no patient in the literature has yet developed CCHF, it is necessary to

exclude this disease and take protective measures. In addition,

patients should be told that ticks can enter the EAC during milking.

To know more about Open Access Journal of

Head Neck & Spine Surgery please click on:

To know more about Open access Journals

Publishers please click on : Juniper Publishers

Comments

Post a Comment