Attention to C-Spine in Craniofacial Trauma-An Update-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF HEAD NECK & SPINE SURGERY

Abstract

The evolution of research and techniques in

management of a trauma patient has reduced the mortality rate

significantly in the golden hour. Severe maxillofacial and neck trauma

exposes patients to life threatening complications such as airway

compromise and hemorrhagic shock. These conditions require rapid actions

(diagnosis and management) and a strong interplay between first level

health care providers, surgeons and anesthesiologists. The cases with

pan facial trauma need at most scrutiny due to proximity to cranial and

cervical structures. In this article an insight into the C-spine

injuries in a pan facial trauma patient has been discussed.

Keywords: C-spine injury; Craniofacial traumaIntroduction

Maxillofacial injuries are frequent cause of

presentations in an emergency department. Varying from simple, common

nasal fractures to gross combination of the face, management of such

injuries can be extremely challenging. Injuries of this highly vascular

zone are complicated by the presence of upper airway and proximity with

the cranial and cervical structures that may be concomitantly involved.

The usual techniques of airway breathing and circulation (ABC)

management are often modified or supplemented with other methods in case

of maxillofacial injuries [1]. Polytrauma patient admitted to hospital

may have injury to cervical spine which is not immediately obvious.

Because patient is neurological normal, with no neck pain or patient is

having distracting pain or patient is unconscious. In case where there

is no clear indication of cervical spine injury, however, patients still

needs to be evaluated for cervical spine injuries because an unstable

cervical spine injury could to delayed & result in neurological

deterioration. Cervical spine injuries have been reported to occur in up

to 3% of patients with major trauma and up to 10% of patients with

serious head injury [2].

Neck Anatomy

It is useful to divide the anatomical structures of

the neck into five major functional groups, to facilitate and ensure a

comprehensive assessment and surgical approach:

- Airway - pharynx, larynx, trachea, lung.

- Major blood vessels-carotid artery, innominate artery, aortic arch, jugular vein, subclavian vein.

- Gastrointestinal tract-pharynx, esophagus.

- Nerves - spinal cord, brachial plexus, cranial nerves, peripheral nerves.

- Bones-mandibular angles, styloid processes, cervical spine.

The platysma defines the border between the

superficial and the deep structures of the neck. If a wound does not

penetrate deep to the platysma, it is not classified as a significant

penetrating neck wound. As transverse cervical veins running superficial

to the platysma may bleed profusely when severed, they are easily

controlled by direct pressure, and can be managed by a simple ligature.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle divides the neck into the posterior

triangle which contains the spine and muscles, and the anterior triangle

which contains the vasculature, nerves, airway, esophagus and salivary

glands [3].

When evaluating penetrating neck injuries, the neck

is divided into three anatomic zones for purposes of initial assessment

and management planning:

- Zone I: Extends between the clavicle/suprasternal notch and the cricoid cartilage (including the thoracic inlet).Surgical access to this zone may require thoracotomy or sternotomy. Major arteries and veins, trachea and nerves, esophagus, lower thyroid and parathyroid glands and thymus are in this zone.

- Zone II: Lies between horizontal lines drawn at the level of the cricoid cartilage and the angle of the mandible. It contains the internal and external carotid arteries, jugular veins, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerves, spinal cord, trachea, upper thyroid and parathyroid glands.

- Zone III: Extends between the angle of the mandible and base of skull. It contains the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries, jugular veins, cranial nerves IX–XII and sympathetic nerve trunk [4].

Cervical Spine and Maxillofacial Trauma

In a complex maxillofacial trauma scenario, cervical spine

fracture should always be considered unless proven otherwise.

Because of the proximity of cervical spine any force of such

magnitude that causes facial fractures can potentially traumatize

the c-spine and its ligamentous attachments [5].

Clinical awareness about the status of cervical spine is

achieved using the most commonly used three evidence-based

decision protocols, Nexus criteria [6], Canadian spine rule [7],

Harbor view criteria [8]. In patients who are awake, clearance

protocol can be effectively implemented by a detailed clinical

examination; however, in an unconscious patient, it is not

possible. The clearance of such patients hinges on clinical

examination, risk, and radiographic examination such as

noncontract computerized tomography, static flexon extension

radiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and dynamic

fluoroscopy [1,9].

Anderson et al. [10] reviewed cervical spine clearance in blunt

trauma patients and classified patients based on their symptoms

and ability to provide a reliable evaluation. Patients are acutely

categorized into one of four groups

a) Asymptomatic: There are two main protocols for

cervical clearance in the asymptomatic patient that have been

and continue to be widely utilized:

i. National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study

(NEXUS) Low-Risk Criteria (NLC) [6] and

ii. Canadian Cervical-Spine Rule (CCR) [7,11].

b) Temporarily non-assessable: Temporarily non

assessable patients have a transient inability to provide a

reliable examination. These patients are expected to resume

their baseline cognitive function and be evaluable within

24-48 hours. Harris et al. [11] reported on this group of

patients and found that most common factors in the category

of temporarily non assessable are drug/alcohol intoxication,

concussion, or pain from distracting injuries. Once the patient

has regained adequate cognitive function and is deemed clinically asymptomatic after a comprehensive examination,

he or she can be treated as such and cleared clinically without

imaging. If a patient is presumed to regain his or her normal

baseline cognitive function within the 24-48 hours time but

cervical clearance becomes more urgent, such as when surgical

intervention is required for other injuries, the individual can

be evaluated as an obtunded patient with advanced imaging.

The most common guideline for this patient population is to

have them undergo a multi-detector CT scan and/or maintain

their cervical collar [11].

c) Symptomatic: Symptomatic patients are those with

neck pain, tenderness, or neurologic symptoms. This

subgroup requires spinal imaging. The various imaging

options include static and dynamic plain radiographs, CT, and

MRI. Each of these various imaging methodologies has specific

advantages and disadvantages, not only regarding sensitivity

and specificity but also in terms of timing and cost. Plain

radiography is one of the earliest imaging modalities and is

currently readily available, fast, and low cost in comparison

to other types of studies. In patients with suspected spine

trauma, plain radiographic evaluation has been shown to

have a wide range of reported sensitivity for cervical spine

injuries ranging from 31.6 to 52% depending on the study

[11,12].

d) Obtunded: Cervical spine clearance in the obtunded

patient is the most controversial aspect and focuses mainly on

whether an MRI is necessary in addition to a negative MDCT.

Though an exceedingly rare incident, isolated neurologic

injury does occur and can lead to significant morbidity. The

percentage of acute trauma patients who are obtunded at the

time of evaluation ranges from about 20 to 30% [3,11,13].

Diagnostic Imaging

Plain radiography

The lateral view is 83% sensitive and 97% specific for

detecting cervical spine fracture. Adding an open mouth view and

AP view increases sensitivity to nearly 100%. The open mouth

view is essential for excluding C1 arch or C2 odontoid process

fractures. The AP view assesses alignment of uncovertebral

joints and spinous processes. Oblique views can be used to

assess facet joints, pedicles, and lateral mass, especially at the

cervicothoracic junction. If the cervico-thoracic junction cannot

be visualized on the lateral view, obtain a swimmer’s lateral view

or a CT scan.

Obtain a CT scan if the patient has normal x-rays but

persistent cervical tenderness and pain. Flexion extension views

are not useful in the acute setting. Pain and discomfort preclude

adequate motion to assess for ligamentous injuries. Only perform

a flexion-extension view on an alert patient under supervision.

Flexion with an occult ligamentous injury may precipitate

neurologic injury [2,14,15].

CT scan

A CT scan is useful for determining the presence and extent

of osseous injury. In fact, it is superior to MRI in this situation.

In blunt trauma patients, CT scan detects 99.3% of cervical spine

fractures. Injuries in the transverse plane may be missed on axial

cuts, i.e., odontoid fractures. It is essential to obtain coronal and

sagittal reconstructions [2,16].

MRI

MRI is indicated for evaluating neurologic deficits and

ligamentous injuries.MRI is superior to CT for demonstrating

spinal cord pathology, intervertebral disc herniation, and

ligamentous disruption. MRI has limited usefulness as the

primary means for initial cervical clearance. The highly sensitive

images of MRI show muscular and soft tissue images that do not

necessarily correlate with clinical instability. MRI is not necessary

if the initial screening CT is negative and the patient does not

demonstrate neurologic abnormalities. CT has evolved to be first

line modality in obtunded patient in a trauma setting. If the CT

is negative, Anderson supports discontinuing the cervical collar.

MRI may find abnormalities even if the CT is negative; however,

these abnormalities are not likely to be clinically significant. The

American College of Radiology advocates both CT and MRI for

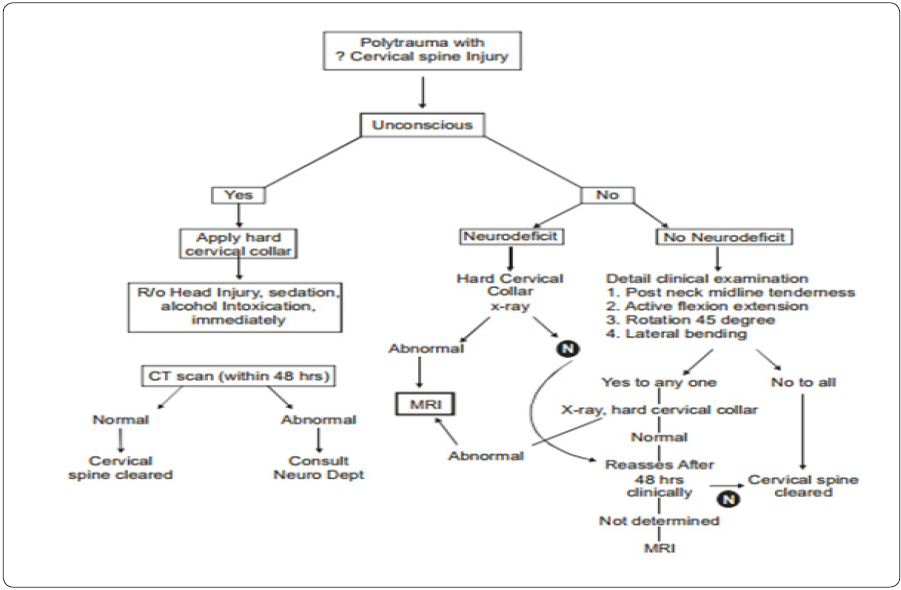

clearance of the obtunded patient [2,17,18] (Figure 1).

Conclusion

There is a continuing debate about the credibility of these

clinical protocols in C-spine without the aid of radiographic

assessment. In a neurologically unstable patient, the cervical spine

must be immobilized irrespective of the injury. The universally

accepted method of C-spine management includes hard collars,

block and straps, and manual axial inline stabilization. These

management methods are rather emotional and lack adequate

scientific basis, especially in conscious patients. However, the

generally accepted fact is that the application of collar protects

and stabilizes the cervical spine temporarily until definitive

management is done. The cervical collar should be applied by

an experienced person or a person trained to do that. It should

be snugly fitted to aid immobilization and while applying care

should be taken not to compress the neck. Improper applications

of collars are implicated in airway obstruction and perhaps

rise in intracranial pressure by affecting the venous return

from the brain. This complicates head injury and increases the

cerebrospinal fluid leakage form skull base fractures and creates

problems during operative repair of maxillofacial injuries. The

gravity of all maxillofacial injuries lies in the fact that they pose

an immediate threat to life because of its proximity to both

the airway and brain. All the same, each case is unique; thus,

the management is exacting even for the most experienced of

professionals. In any given scenario, no treatment approach can be sure and flawless. The need of the hour is a multipronged

approach requiring a partnership between several departments.

While new technology and material developments [19] have

helped ease the situation, it is the timely intervention, she

er skill,

and presence of mind of emergency personnel, and surgeons

that counts.

To know more about Open Access Journal of

Head Neck & Spine Surgery please click on:

To know more about Open access Journals

Publishers please click on : Juniper Publishers

Comments

Post a Comment