Simulation in ENT- Is There a Place For It?-Juniper publishers

Introduction

Airway emergencies are a common presentation in the

emergency department, with the incidence reported to range between 2%

and 14.8% Kovacs et al. [1]. In the vast majority of cases, ‘difficult

airway’ presentations are managed successfully by emergency medicine

doctors Wong et al. [2]. While anaesthetic staff on the whole manage the

remainder, surgical doctors (especially those working within ENT

surgery) are often involved in cases that require invasive interventions

such as tracheostomy or surgical cricothyroidotomy Awad et al. [3].

Furthermore, it is often the most junior member of the ENT team is first

to attend to those patients requiring emergency on-call airway

services; frequently without immediate senior supervision or support.

Despite this, there is currently no formal curriculum

in airway management for core surgical trainees (ISCP, 2013) and as

such, training is highly variable. Awad et al. [3] conducted a survey

assessing competence of emergency airway management amongst one hundred

ENT surgical house officers in the United Kingdom and reported that only

54% of respondents felt their training in this area was adequate and

felt confident to provide emergency airway services. Furthermore, the

authors found that attendance at ALS or ATLS courses correlated poorly

with trainee confidence and perceived adequacy of training.

While there is a large availability of airway

management courses, the majority appear to be aimed at the anaesthetic

audience. Of those available to alternative groups, most are either too

basic or too advanced to meet the requirements of the core surgical

trainee working in ENT [4].

Rationale for simulation

Training in medicine has traditionally been based

upon an apprenticeship model whereby the novice is taught by an ‘expert’

(usually within the clinical arena); ultimately becoming master

craftsman him or herself Chur H et al. [5]. However, such a model has

been significantly challenged by a number of factors including the

European Working Time Directive and its impact on available training

time, variability in trainee exposure and increased emphasis on patient

safety Motola et al. [6]. Such concerns may in part be responsible for

the exponential rise of simulation training within medical education

over the past two decades.

Simulation-based medical education (SBME) enables

trainees to learn within a safe, controlled environment without

compromising patient safety [7-9]. In addition, SBME offers the

opportunity for formative assessment and feedback. The basis of

simulation is underpinned by the concepts of deliberate practice and

mastery learning; the former refers to the identification and practice

of specific components of a skill, which provides immediate feedback to

promote improvement Ericcson [10]. Ericcson (2004) argues that

deliberate practice is critical to the acquisition of motor skills and

pivotal to the transition from competency to expertise. Indeed,

Ericcson’s research highlights that deliberate practice is a more

powerful predictor of expert performance than is academic aptitude or

experience. Deliberate practice is of particular importance when

considering motor skills that are rarely performed (i.e. emergency

surgical cricothyroidotomy) and thus offers little opportunity for

practice within the clinical setting. The concept of mastery dates back

to 1960s Motola et al. [6] and has its origins in engineering education.

In essence, mastery learning is competence-based

education that aims to ensure all learning objectives are attained by

all learners; eliminating variation in trainee outcomes as far as

possible Wong & Kang [11]. However, it is acknowledged that learners

may take varying amounts of time to achieve mastery [12]. A number of

authors have documented various positive translational outcomes of SBME

including reduced length of hospital stay, fewer intensive care

admissions as well as reduced health care costs Barsuk et al. [13]. For

instance, a recent systematic review undertaken by Cook et al. [14]

comparing mastery SBME with traditional training within healthcare

reported that SBME had a large and statistically significant effect upon

skill acquisition and a moderate effect upon patient outcomes.

Curriculum

A hybrid SBME program that incorporates an initial

didactic lecture, skill stations and intermediate-fidelity simulation

scenarios with the focus on the recognition and management of airway

compromise, aimed specifically at junior surgical

trainees working within ENT surgical departments is proposed.

As a prerequisite, participants should be working within an ENT

department and have completed both ALS and ATLS. Although,

a number of airway management courses are already currently

available, these appear not to include all the elements outlined

above. Furthermore, the vast majority may be arguably too basic

for the junior surgical trainee working within ENT surgery (i.e.

ALS), or indeed too advanced; being aimed at anaesthetic or

ENT specialty trainees. The course will not only aim to teach

participants the technical skills required to manage patients

with airway compromise, it will also address the non-technical

elements through the use of simulation scenarios.

This will be performed in a three-step manner whereby

participants can build open their knowledge by first providing the

opportunity to learn or review underlying theoretical principles

of airway management, followed by the practice of specific skills

or procedures, before finally applying such knowledge and skill

later within the simulation scenarios. Windsor [15] outlines

a hierarchy of surgical skill acquisition beginning with basic

or core skills, becoming more complex and automatic with the

attainment of procedural and non-technical skills. Professor

Windsor, a surgeon himself, emphasises that in traditional

surgical training, the trainee is expected to master skills from

all such domains simultaneously. He follows further that SBME

enables trainees to learn appropriate skills at a time that is

appropriate to their experience. This is somewhat in keeping

with Bloom’s Taxomony of Learning 1956 cited in Amer [16] that

outlines three educational domains as cognitive (knowledge),

psychomotor (skills) and affective (attitudes) and follows that

educators and the learning activities they use should facilitate all

levels of learning commencing with the most basic and building

to a level which ultimately fosters high cognitive education [17].

Skills stations

The trainees will rotate through three skills stations in small

groups. Each station will be led by one senior clinician and will be

interactive to enable participants to discuss and clarify ideas and

issues. Each station will provide the opportunity for ‘hands on’

practice in basic airway skills (simple adjuncts) and intubation,

surgical airways (cricothyroidotomy and tracheostomy) and

fibro-optic nasoendoscopy. Skills will be performed on cadaveric

head and neck specimens [18-20].

Intermediate-fidelity simulation

Skill stations will be followed by a series of simulation

scenarios using a Sim Man patient simulator; all with the theme

of management of patients with rapidly deteriorating airway

problems. The scenarios will be formulated from a combination

of real life examples and learning needs assessments.

Participants will undertake simulation scenarios individually,

playing their true role as ENT surgical house officers and will be

assisted by other participants and facilitators who will assume the role of nursing and anesthetic staff to increase the realism

of the scenario. Realism is important in fostering the notion of

suspension of belief whereby participants ‘buy into’ the scenario

as a real life clinical situation [21-23]. Each scenario will last 8-10

minutes in duration and will be preceded by a concise briefing in

the form of a referral or handover. The remaining participants

will follow the progress of each scenario via a live video feed.

The simulation scenarios will not only provide an opportunity

for participants to transfer and apply the knowledge and skills

acquired from the previous activities it will also assess candidate

ability to function as an effective team member. In modern

medical practice, there is increasing emphasis being placed upon

the impact of the clinical environment, wider team dynamics

and human factors Marshall & Flanagan [24] and it has been

shown that effective team working is an essential component

of care delivery and overall patient outcomes. In particular,

communication, or more specifically, miscommunication was

indicated as a root cause of almost 70% of significant events Joint

Commission of Sentinel Events [25]. Despite this, undergraduate

and early surgical education has traditionally failed to address

the skills required to work effectively within teams; focusing

primarily on knowledge and acquisition of technical skills

Flanagan et al. [26].

Debriefing and feedback

Feedback is an integral aspect of learning within SBME. Van

De Ridder et al. [27] define feedback as an activity that involves

the giving of specific information around a trainee’s observed

performance given with the intent to improve their performance.

Debriefing is a specific form of feedback employed in SBME

and has been described as the single most important part of

simulation training Rall et al. [28]. The importance of debriefing

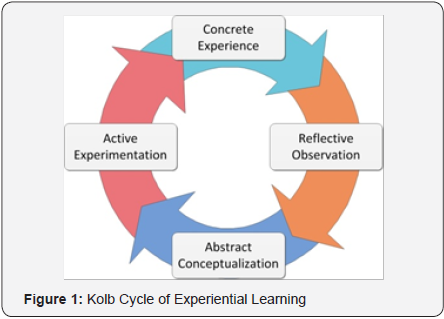

and feedback can perhaps be explained again by the work of

Kolb’s four-stage model of experiential learning (1984 cited in

Motola et al. [6]) that reinforces that enhanced learning occurs

when participants are given feedback to form the basis of a postreflective

process where they are able to make sense of events

through analysis and subsequently implement new ideas and

theories to facilitate improvement (Figure 1).

Savoldelli et al. [29] support this highlighting that isolated

simulation encounters without feedback often fails to lead to

trainee improvement, particularly in the domain of non-technical

skills. It must however be borne in mind that feedback has the

potential to be demoralising and counterproductive; having a

negative impact upon learning if delivered ineffectively Wulf et

al. [30]. Given the importance of debriefing, a significant amount

of time will be allocated to undertaking this process (up to 40

minutes for each scenario) and will be undertake as a group

activity facilitated by two instructors [31].

Conclusion

Although it is clear that simulation in health care can

be effective, to date empirical evidence around aspects of

development, instructional design as well as implementation of

simulation programs is largely lacking. With specific reference to

SBME in surgery, there is strong evidence that simulation is an

effective educational activity for the acquisition of surgical and

non-technical skills. More specifically, SBME is also proving to

be important in airway management education and as such may

be an invaluable adjunct to the current ENT specialty training

curriculum. Within core surgical training where no formal

curriculum exists around acute airway management however,

simulation may offer the only opportunity for formal teaching

before junior doctors working in ENT are faced with a real life

patient with airway compromise.

To know more about Journal of Head Neck please

click on :

Comments

Post a Comment