Latex Allergy: Overview and Recommendations for the Perioperative Management of High-Risk Patients-Juniper Publishers

Juniper publishers-Journal of Head Neck

Latex is a natural substance that comes from the sap

of the rubber tree. It is a material widely used in the manufacture of

domestic, industrial and especially medical products [1]. The prevalence

of latex allergy in the general population is estimated between 0.8 and

6.5% [2], and the repeated exposure to this material is the most

significant risk factor for its development [3]. Among the main risk

groups are health personnel, where the incidence reaches 17%, and

patients with spina bifida where 73% incidence has been described [4]

(Table 1). Factors as age, race or sex are not associated with an

increase in risk.

Worldwide, it is estimated that in one of every 3.500

to 20.000 surgeries an anaphylactic reaction occurs, which

represents about 9% to 19% of all surgical complications, with a

mortality varying between 3% and 9% [5]. About 50% of the medical

devices contain latex [6], so it is not a surprise that this material is

the second cause of perioperative anaphylaxis, being responsible in the

12 to 16.7% of cases [7]. Fortunately, this incidence has decreased

significantly since hospitals and outpatient surgery facilities have

adopted latex-free policies [5]. Based on this background, latex allergy

is a condition of special interest to the healthcare professionals.

This review of the literature seeks to expose the relevant basic

concepts about allergic reactions to latex, as well as to generate

guidelines for the perioperative management of sensitized patients.

Sensitization mechanisms and immunological associated to latex reactions

Latex allergy is associated to any

immunologically mediated reaction to this material, associated with

clinical symptoms. Since the 1980s, there has been an increase in the

incidence of allergic reactions to latex, associated with the

introduction of mandatory use of gloves within universal precautions in

the prevention of infectious diseases such as HIV, Hepatitis B and C

[1,3,8]. Sensitization depends on factors such as the route, dose,

frequency of exposure, and individual susceptibility [2,4,9]. Exposure

may occur as a result of direct contact with skin or mucous membranes, a

wound inoculation, or ingestion.

Another type of exposure occurs when the latex proteins

bind to the dust that contain these products, volatilizing during

the placement and removal of gloves, being inhaled and to enter

the respiratory tract [10].

It has been shown that these particles can remain suspended

in the environment for up to 5hours [4,11]. The amount of

exposure needed to sensitize a person is unclear, and the

threshold required to trigger an allergical response varies

considerably among individuals [12,13]. Is possible to describe

three types of allergic reactions to latex:

Irritant contact dermatitis: It is the most common type

of allergic reaction. Can develop within minutes or hours after

exposure, due to mechanical or chemical skin irritation by the

components used in the product manufacturing process [3].

Clinically it is characterized to present as pruritus, rash, scaling,

burning sensation, inflammation or blistering [8]. No previous

sensitization is necessary for the development of dermatitis,

but this condition facilitates the progress of an immunologically

mediated hypersensitivity reaction, because the lost of skin

integrity favors the direct exposure to allergens [14].

Allergic contact dermatitis or type IV hypersensitivity

reaction: Reaction mediated by cellular immunity. It occurs

between 6 and 48hours after contact with latex, but is usually

produced by other allergens from the chemicals used in the

production process [8]. T lymphocytes are sensitized and

infiltrate the contact zone on the skin [1]. The symptoms are

similar to those of irritative contact dermatitis (erythema,

vesicles and desquamation) and do not require a history of

previous contact to manifest itself [7].

Type I hypersensitivity reaction: It occurs after minutes

of exposure, either by the cutaneous, mucosal or aerial route. It

requires prior sensitization with latex proteins and production

of IgE antibodies. Clinically, it can present as a localized urticaria

to a frank anaphylactic reaction. Moderate reactions include

rhinitis and conjunctivitis, and are more likely to occur due air

exposure or skin contact.

Eighty percent of the reactions associated to latex correspond

to contact dermatitis or type IV hypersensitive and occur mainly

in response to chemicals used in the manufacture of these

products [12]. Only type I hypersensitivity corresponds to a

response to proteins in the latex [8]. This reaction is less frequent

but can generate large complications and life threatening if it is

developed during the perioperative period.

Identification of allergic patients or at potential risk

High-risk populations are those that are frequently exposed

to latex elements, such as patients undergoing multiple surgical

procedures, health personnel, rubber workers, and individuals

with a history of atopy [1]. These populations are at increased

risk of developing more frequent and severe allergic reactions

[5]. In particular, patients with congenital malformations of

the central nervous system give especial interest. In patients with spina bifida, incidence of latex allergy has been reported

in 35% to 73% [4,15]. These patients have also show increased

sensitization to latex protein and a significant increase in levels of

fully and specific latex IgE from the perinatal period, which could

be associated with the occurrence of allergy in the future [16].

Another example is patients diagnosed with myelomeningocele,

with an estimated incidence of 19.51% latex allergy, and 18% of

sensitized patients [17]. The most important risk factor to the

development of allergy in these cases is the history of 5 or more

surgical interventions [17,18].

Deep clinical history minimizes the risk of new exposure

in sensitized individuals during prior medical and dental

procedures. The anamnesis should emphasize on risk factors,

such as exposure to latex, spina bifida, reconstructive urologic

surgery, multiple surgical procedures, intolerance to latex

products [balloons, gloves, preservatives, dental rubber dams),

allergy to fruits, history of intraoperative anaphylaxis of unknown

cause, or health personnel with a history of atopy [4] (Table

2). It is estimated that in 30% of cases of anaphylaxis, there is

a suggestive history of previous reactions [7]. Individuals with

allergies to some specific foods are at increased risk of develop

allergic reactions to latex. Although the mechanism is not clear,

some proteins present in certain fruits may act similarly to the

latex allergenic proteins and produce sensitization [1]. It has

been reported that between 21.2% and 86% of patients with

documented allergy to latex also had a food allergy. Some of

the foods that could produce cross-reaction with latex include

banana, avocado, kiwi, grapefruit, papayas, almonds, chestnut,

pineapple and tomatoes among others [6]. Allergy to these foods

may precede allergy to latex or vice versa.

Prevention Strategies

The best treatment is to avoid exposure [1,12]. The incidence

of anaphylactic reactions to latex has decreased due to the

identification of high-risk patients, better diagnostic tests and

preventive measures [3]. For patients with spina bifida treated in latex-free environments, incidence of latex allergy seems to

be similar to the general population. More specifically, it has

been reported an incidence of 5% sensitization and 0.8% of

allergies in patients with spina bifida hospitalized in latex-free

environments, versus 55% and 37%, respectively, in patients

managed in environments without restriction to exposure to

latex [19].

Given that in most cases is not feasible to have 100% latex-free

environments, is essential to at least generate a safe environment

for patients with prior allergy history to this material. This is

usually sufficient and is more achievable than an environment

completely free of latex [11]. These general measures include

adequate identification of allergic patients, proper labeling

of products formulated with latex and use of latex-free gloves.

Among the general recommendations for health establishments

is important to educate staff, establish clear protocols for the

management of these patients, have a latex-free cart available

and check the latex contents of the entire surgical team.

The antigen content in latex products can vary significantly.

Products manufactured with an “immersion” process (eg

gloves and preservatives) have the highest levels of allergens,

whereas dry rubber (eg tires, rubber seals, plugs and plugs of

vials and syringes) are less allergenic [8]. It is important to note

that products labeled as hypoallergenic have fewer chemicals

responsible for causing allergic reactions, skin irritation and

dermatitis, but this labeling is not related to the latex content of

these products [11,14]. The two main prevention strategies are:

Use of latex free gloves: There is important evidence

that latex gloves are the main source of allergens in health

care settings [12]. These have been the most popular given

their characteristics, which include strength, elasticity and

superior protection qualities. It has been shown that the level

of aeroallergens in the environment is strongly correlated with

the use of gloves with high content of allergens and dust, total

number of gloves used and hours of activity in the environment.

Studies have shown that changing gloves with high dust content

by gloves with low amounts or dust-free (which are low in

proteins and allergens) results in a significant reduction of

aeroallergens and a dramatic decrease in the incidence of latex

allergy. It has also been reported that after removing latex

gloves at work sites, the levels of aeroallergens are reduced to

undetectable levels after 24hrs [8].

Concern about latex allergy has led to alternatives such as

polyvinyl chloride (PVC) gloves or nitrile gloves. It seems to be

that PVC gloves filter more than latex gloves (63% filtration

in PVC gloves, versus 7% latex gloves), but on the other hand

nitrile gloves have shown a better performance than those of

PVC. Unfortunately routine use has received some resistance

[12] and latex gloves continue to be a cheap alternative, offering

appropriate protection and other essential qualities for safe and

effective performance.

Pre-medication: The role of pre-medication with H1

antagonists and corticosteroids is not well defined. These

medications may help to decrease non-IgE-mediated reactions.

However, they do not prevent IgE-mediated immune reactions

[7,12,20]. Avoiding exposure to the allergen is the only way to

avoid an anaphylactic reaction.

Surgical Management Protocol for Patients with Latex Allergy [2,4,13]

The following measures are aimed at promoting safe care

during the perioperative period in patients at risk for an allergic

reaction to latex, either by medical history or because they have

positive laboratory tests:

Preparation of the surgical theater and preoperative period [2,13]- The procedure or surgery should be scheduled first thing in the morning, when the levels of aeroallergens are lower.

- Install a label on the door of the operating room that identifies the patient as allergic and to the room as latex-free.

- The day before surgery, remove all products containing latex (reserve bags, endotracheal tubes and laryngeal masks that are not latex-free).

- Cleaning staff of the surgical room should not wear latex gloves. The day of the surgery, the surfaces should be cleaned again to remove the suspended powder.

- When appropriate, the mattress should be protected with double bed sheet.

- Cover all monitoring devices, cables/tubes (oximeter, blood pressure, electrocardiogram) to avoid direct contact with the skin.

- Products sterilized in ethylene oxide must be rinsed before use. Residual ethylene oxide reacts and may cause an allergic response in a patient allergic to latex.

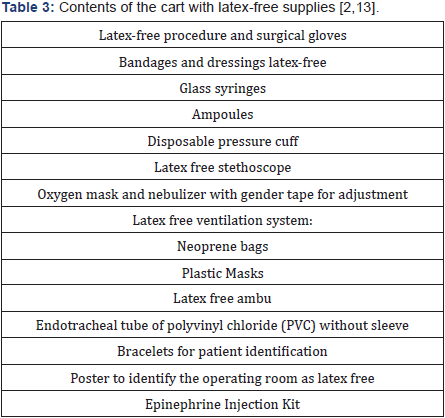

- A cart with latex-free supplies (Table 3) should be available inside the operating room.

- The operating room should be adequately equipped

to handle an unexpected anaphylactic reaction and have

immediate availability of epinephrine.

- Allergic patients should be identified at the time of

admission with: a bracelet, in the medical history and in the

sheets of nursing.

- Before the pressure is taken, the arm should be covered

with a cotton mesh and auscultated through it, avoiding that

the stethoscope has contact with the skin.

- The patient should wear a cap without elastic and

gender boots.

Intraoperative period

- All the surgical team should wear latex free gloves.

- The traffic inside the surgery room should be minimal.

- Do not use penrose drains, latex bands, latex irrigation

elements (eg irrigation pears).

- Latex-free or glass syringes should be used.

- Medications should be preferred in glass ampoules. If

not available, remove the rubber stoppers before preparing

the medication.

- Medications should be prepared immediately prior

their administration to minimize contact with the syringe

plunger.

Postoperative period

- The postoperative period should be performed in the

room prepared for the patient or inside the same operating

room.

- All departments involved must be informed of the

presence of patients allergic to latex, so that they can take

the necessary precautions to protect them.

Detection and management of an allergic latex reaction

Since the allergen is generally absorbed slowly from

the

surgeon’s glove, the reaction usually occurs about 30 minutes

after contact with the skin and mucous membranes during the

maintenance of anesthesia, not during the induction period.

However, the actual start of the reaction may range from 10 to

290minutes [13]. This interval will depend on the sensitivity of

the patient, amount of allergen absorbed and the contact surface

(absorption is faster through the peritoneum or vaginal mucosa

than through the skin) [7]. Except for these characteristics, latex

reactions are similar in their manifestation to those reactions

caused by other agents during surgical and medical procedures

[2] such as muscle relaxants or antimicrobials.

The management of an intraoperative anaphylactic reaction

is well-documented [4,5,13,21] and includes pharmacological

and non-pharmacological measures according to the clinical

presentation, course of the condition and the context in which

anaphylaxis occurs. In the particular case that the reaction

is suspected to be caused by an undiagnosed allergy to latex,

the following measures should be incorporated as part of the

management:

- Stop or minimize the absorption of the agent (consider

the variety of possible routes of exposure).

- Remove all products containing latex and change to

latex-free gloves.

- Place an allergy alert to the latex in a visible place at the

entrance and inside the surgery room.

- Complete the study of the patient after the reaction.

In mild cases, spontaneous recovery may be observed even in

the absence of any specific treatment. In such circumstances, lack

of proper diagnosis and evaluation can lead to fatal re-exposure

[20]. Any suspected hypersensitivity reaction during anesthesia

should be extensively investigated through a detailed history

of the reaction, with emphasis on concomitant pathologies,

known allergies, previous anesthetic history and the stage of

anesthesia were the reaction occurred, in addition to performing

laboratory tests according to each case [7]. Immediate tests have

been designed primarily to determine whether or not an allergic

mechanism is involved in the reaction, while late testing seeks to

identify the drug responsible and possible alternatives to its use

[20]. Among the tests available for the study of latex allergy are:

Serum tryptase: Indication of mast cell activation. It rises

in mediated and non-IgE mediated reactions. A concentration

above 25mcg/ml might suggest a type I reaction [5,7]. The

recommendation is to take serial samples immediately, at 2, 6

and 24 hours, after the reaction. It has a sensitivity of 64% and a

specificity of 89% for anaphylaxis. The absence of a high tryptase

does not exclude an anaphylactic reaction.

Serum-specific IgE: The recommendation to perform

this test after 4 to 6 weeks and before 6 months of the event.

Immediate measurement could give a false negative. The

sensitivity of IgE tests is variable; for latex is about 92%.

Skin tests: They can be done up to one year after the event, but

not immediately to avoid a false negative. The recommendation

is to wait 4 to 6 weeks after the reaction.

Prick test: Evaluates the sensitization to the latex, with a

sensitivity and specificity close to 100% [4]. Only IgE-mediated

reactions can be studied with cutaneous tests [7], since they do

not identify non-immunologically mediated reactions [5].

Patch test: Is recommended for the study of latex contact

dermatitis. Additives used in the glove manufacturing process

should be included, since delayed hypersensitivity is rarely due

to allergens characteristic of unprocessed latex [14].

Conclusion

Although achieving completely latex-free environments is

unrealistic, every effort should be made to minimize the risk

of sensitization, especially in high-risk groups such as patients

with congenital malformations requiring multiple surgical

interventions during their early years of life. In addition, it is

important to consider that achieving an environment with low

levels of allergens is an issue that not only involves the safety

of the allergic patient. The implementation of these measures

has a significant impact on the sensitization of exposed health

personnel and barriers to protection against infectious diseases.

The management of latex allergy should be approached from

different perspectives and multidisciplinary support should be

obtained to:

- Establish policies for the identification and care of patients with known allergy to latex;

- Develop policies and procedures for health workers with latex allergy;

- Provide environmental control and resource management to minimize unnecessary exposure of patients and staff to materials with a high content of latex antigens; and,

- Promote the ongoing training of patients and employees on the topic of latex allergy.

To know more about Journal of Head Neck please

click on :

Comments

Post a Comment